Podcast (top-left-corner): Play in new window | Download

Editor’s Note: The Greylock Glass pays to have rough transcripts of interviews produced. We attempt to remain as faithful as possible to the speakers’ original meaning, and apologize for any errors of transcription. That said, even the imperfect transcription we perform is costly. Please support us financially by becoming a member or making a one-time contribution to help us continue to provide this service.

Top Left Corner: This is the top left corner at The Greylock Glass. And this is Episode #173 of the Top Left Corner right here on The Greylock Glass GreylockGlass.com the Berkshires’ mightiest independent alternative news thing. I’m your host, Jay Velázquez, and I do thank you for tuning in today. At least the day that I hit record on this episode is Tuesday, October 4th, 2022. And it is another great show. It is a part deux. It’s a continuation of episode 172 in which we spoke with Larry Parnass, the Berkshire Eagle’s managing editor for Innovation, who discussed the issue of source confidentiality as it pertains to the investigation that he has been has been ongoing, that he’s been in charge of into clergy abuse that went on during the 1960s and has resulted in. A court case, John Doe versus Roman Catholic Bishop of Springfield, a Corporation, Sole and others. And the situation is somewhat resolved because I’ll give you a spoiler. The court order that we’ve been expecting came down today, just a few hours ago, and we’ll talk a little bit about that. But basically the situation is this. As you heard in episode 172, the Diocese of Springfield, in an effort to…Well, I guess protect itself. Defend itself. At least that’s the theory. They tried to compel Larry Parnass to turn over all of his notes, any documents that might be related to the investigation that he’s done. The judge originally and this is Karen Goodwin, justice of the Superior Court, Hampton County, said no, everything.

RELATED: Top Left Corner #172: The Berkshire Eagle’s Larry Parnass on protection of confidential sources

Op-Ed: “On The Berkshire Eagle and “Reporter’s Privilege”

Judge in clergy rape suit says diocese can’t have information that reveals confidential Eagle sources

Top Left Corner: No way, Jose. That would be I think she called it a classic fishing expedition and said maybe she’d consider a certain amount of stuff that that Mr. Parnass could be compelled to surrender. Big mess. People have been sitting on pins and needles. It is a case that has been watched. I know personally know of at least one college professor that is teaching this to their students right now as the case sort of unfolds. In any event, the the part deux was already planned. I had interviewed a local journalism scholar, Bill Densmore. He’s a friend of mine, and he has a lot of great things to say, but a lot of insights that he brings to the table from his years of of both doing journalism and teaching it. So this is a very great to have him on the show, even though just a few hours ago, the court order, the memorandum and order on motion for reconsideration has been returned. Judge Goodwin heard Larry Panos basically appeal his request that certain elements of the original decision be revisited. And she did so. And I’m going to I’m going to play for you the spoken version of that. Of that that memo and order. I’m not going to speak it. I’m going to let my lovely and charming automated vocal assistant do that for me. But we’re going to hear that right after this message from. FEMA on emergency preparedness. And then we’ll hear from Bill Densmore himself.

FEMA PSA: If you can plan barbecues and weddings, you can plan to protect yourself from a natural disaster. Sign up for local alerts. Prepare an emergency kit and make a family communications plan. Get started at ready.gov/plan brought to you by FEMA and the Ad Council.

Memorandum and Order on Motion for Reconsideration

Court order from Judge Karen L. Goodwin: John Doe versus Roman Catholic Bishop of Springfield, a corporation, Soul and others. Memorandum and Order on Motion for Reconsideration. Berkshire Eagle managing editor Larry Parnass has moved for reconsideration of the Court’s July 29, 2022 order, allowing in part and denying his party the defendant’s motion to compel Parnass to provide documents and testimony. The court’s order limited the area of inquiry and provided what it thought was a mechanism for Parnass to protect the identity of confidential sources. Parnass machine asserts one He cannot produce documents or provide testimony about information provided by confidential sources without revealing their identities and to the court did not properly weigh the defendant’s need for the information against the harm disclosure would pose to the free flow of information. On the latter point, Parnass specifically faulted the court for not requiring the defendants to establish that they had exhausted all other sources of information.

Court order from Judge Karen L. Goodwin: Addressing the second point first, Parnass argues that the defendants have not shown they sought the requested information from the many witnesses, John Doe statements to Kevin Murphy and a review board. While the court agrees that the defendants have not made such a showing, Massachusetts law does not require that they do so. See Dow Jones and Company versus Superior Court 364. Massachusetts 317 320 1973. See also can be versus American Medical Response No.18 CV 30050 MGM 2019 Wll 1118103 DD Massachusetts 2019 Noting that the Supreme Court has rejected an automatic requirement that non confidential sources be exhausted. The court conducted the necessary balancing test in its initial order.

Court order from Judge Karen L. Goodwin: Parnass argument on the first point, however, has caused the court to rethink its order as to information from confidential sources. In light of Parnass affidavit stating that he cannot protect the identities of confidential sources simply by redacting their names. The court revises its order to apply only to non confidential sources in the event the defendants wish to press their motion as to confidential sources, they will be required to demonstrate their efforts to obtain the information directly from those attending the meetings with Kevin Murphy and or the Review Board.

Court order from Judge Karen L. Goodwin: Further looking ahead toward the trial, the court is open to requiring that parties disclose whether any of the individuals identified as trial witnesses were confidential sources, and if so, to produce the information those sources provided to him. In summary, the court revises its July 29, 2022 order to reflect it as compelling only information provided by non confidential sources as to what they told Parnass about DOE statements to Murphy and or the Review Board.

Court order from Judge Karen L. Goodwin: Karen L. Goodwin, Justice of the Superior Court, dated October 3rd, 2022.

NTRVW: Bill Densmore

Top Left Corner: And with me on the line is Bill Densmore, who is known throughout Berkshire County as a scholar of journalism and someone who knows the local scene. The local news seemed pretty darn well. Thanks so much for being on the show, Bill.

Bill Densmore: Glad to be here.

Top Left Corner: Now, let’s before we dive too too much into the conversation at hand. For those people who don’t know you, give us a little bit of a rundown of your background in journalism and and how you came to to. Well, I guess at the very least become a consultant for the eagle as as they sort of transitioned from a sort of venture capitalist company back into an independent entity.

Bill Densmore: Right. Well, I I’m now a member of the editorial advisory board of the of the Eagle, and that’s a great vantage point to follow what our local paper is doing. And in the briefest way I can think of possible us might. As to my background, I was editor of the UMass (The University of Massachusetts Amherst) Daily when I went there a long, long time ago and then worked for the Associated Press trade publishers. My wife and I together owned and published The Advocate News weekly for the Berkshires in southwestern Vermont for nine years in the eighties and early nineties. And mostly since then, I’ve been doing research on the future and sustainability of journalism for UMass, for the Rentals Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri, and working with a nonprofit that I set up with some other people called the Information Trust Exchange Governing Association. What that is, is another story, but not relevant necessarily to this conversation.

Top Left Corner: Hmm. Well, hopefully we get a chance to talk about that one day because and you’ve mentioned it to me before, and it’s it’s there’s some exciting developments in journalism. I know that you have you have done a lot of research into nonprofit journalism, which is an interesting and exciting development that more, more entities are pursuing because it seems to be a way for them to survive. So let’s set let’s talk a little bit about the history of of this story. This goes back to at least as early as 2019, when Larry Parnass began as part of a sort of eagle eye investigative function. He began looking into claims of clergy abuse within the Springfield Diocese. Were you paying attention at that time?

Bill Densmore: Only. Only as much as a casual reader might have?

Top Left Corner: Sure. Well, it’s not that. It’s not certainly not. The first case that made a lot of news. Boston was probably the the the what put the issue into national attention, I would say, because there’s just so much and continues to be so much that comes out there really damaged the Catholic Church across the United States when revelations of you know at first many of the people involved in trying to cover it up suggested that if it happened at all, it was just very rare or very, you know, occasional. But come to find out, it wasn’t rare, it wasn’t occasional. There really was a tremendously broad and and painful history of clergy taking advantage of young people in their flocks. When you come to an issue that is this personal and this painful, it is not any surprise that some people don’t want their identities known. So maybe from a general standpoint, Bill, what is common practice when it comes to working with a source who wants to remain anonymous? What is what what are some standard things that a journalist would try to do?

Bill Densmore: Well, I haven’t been. I tell people I’m somewhat of a journalist on sabbatical because I haven’t been in a newsroom cranking out stories for many years. But I also did it for many years before that. And I don’t think the basic issues have changed over the 40 years or so that I’ve been doing journalism. It’s it’s the case that sometimes people will tell you. More. Stuff about a story if you promise them some kind of anonymity. And that anonymity could be. A I. You’re giving me permission to use the. The. Information you’re giving me, but I can’t associate it with your name or even hint who gave me the information. In other words, I’m going to have to use the information unattributed and just call it a source. That’s the most aggressive form of of shielding the source. Then it could be just I’m going to be able to say that I talk to you, but I can’t quote you directly. And sometimes politicians will do that because they really don’t want to be hung on specific words. And and there’s all kinds of negotiated arrangements in between those that a journalist might work out with a source. And my understanding, just from what I’ve read of the accounts in the eagle of this situation is that a particular individual was promised anonymity and would not it was promised by the newspaper in the person of Larry Parnass, but acting on behalf of the newspaper, presumably he was the source was promised that he wouldn’t be named or otherwise identified in any story that was written.

Bill Densmore: And so that sets up always and and fairly frequently, actually some a challenge between a private citizen who brings a libel lawsuit or a public official who or prosecutor brings a case or a prosecutor, as in this case, who has got another case going related to the priest abuse issues and the prosecutor or the defendant’s lawyer or the plaintiff’s lawyer. I can’t remember which it is in this case feels that they can get a better picture of the situation involving their client or they’re the accused by. Learning the identity of the person that Larry Parnass spoke to and. So it’s just routine for lawyers to want that information and to seek it. Then you get this conflict based in. Precedents around the First Amendment. And the question is what what happens next? What yields does the reporter have to give up? You have to reveal the identity of their source. Does the person who’s seeking that source his name, figure out another way to get the information they need to manage their court case? Or does something in the middle happen? And a lot of times what happens in the middle historically is the source will decide to allow the reporter.

Bill Densmore: To be unbound ethically from the promise the reporter gave so that the reporters are released from that obligation of confidentiality. And then the reporter can say, Oh, well, it was so-and-so, and then deported reporters off the hook because the lawyer who’s wanted that person’s name now knows their name and they go and talk to them or subpoena them or do whatever they’re going to do to manage their case. If the source is unwilling to release the reporter, which is probably the case at the moment. Now in the Eagle, Larry Parnass matter. Then you have this clash of competing values around the right of somebody to get all the the. Data they need to defend themselves in a case. Right. And the reporter’s moral and ethical obligation to respect and maintain the promise they made. And I don’t know yet what’s going to happen. I mean, I don’t know what’s going to happen in this case just yet. I mean, it’s going to have to be negotiations behind the scenes probably, or the judge may eventually rule that that testimony of the unnamed source is not necessary for the trial. And then that becomes a matter for sorting out some day when the case is heard on appeal.

Top Left Corner: Well, Heather Bellah wrote last week in The Eagle that a judge, Karen Goodwin, who had originally called the diocese. Seeking everything that Larry Parnass had a fishing expedition. I think it was a complete fishing expedition or a classic fishing expedition, she said, because they wanted everything. I mean, they wanted notes. They wanted probably phone records. I mean, they wanted just everything. And that obviously would have been damaging to to the story for sure. This and the lawyer, you were correct. His name is McDonough. I think it’s Michael McDonough said that. Yes. In fact, it’s all we care about. Just making sure that. That. The source that the statements made by the source to Larry Parnass are consistent with the statements that the source made to the dioceses when that person reported this this abuse. So the diocese claims that there they are excuse me, that the the according to Heather’s Heather Bella’s work, quote, the diocese found the John Doe’s allegations against two other priest credible and have been supportive and paid for his therapy. Mcdonough said So I don’t know they know who this person is. So it’s not a matter of not knowing who it is. It’s a matter of. I guess, basically subpoenaing them and putting them on the hot seat, which is precisely what this person is trying to avoid, a very public exposure. Now, there are a lot of reasons why people might not want to admit that they have been a victim of clergy abuse. It could be that it’s simply too painful. It could be that they have a very public position that they feel would be threatened if the word were to get out. It could be any number of reasons. And at the moment in Massachusetts, there is there is no so called shield law that allows a reporter source confidentiality protections. What can you tell us about what shield laws typically do or don’t do to help preserve this confidentiality?

Bill Densmore: I I’m probably not experienced enough in the law to answer that in in a way that would be trustworthy information, I’m afraid. I just don’t I just haven’t kept up with the with the status of shield laws. There was a time when I was fairly up to date on that, but I’m not now.

Top Left Corner: Well, I’m sure that we can probably find somebody at UMass. They often are very, very keen on speaking to these issues. If you can get the right person on the line. They actually have a great reporter sourcebook that they that they publish or they used to publish anyway, whenever you needed that. So I’ll try to find that. But in general, I know that states have different versions of of shield laws and it is essentially just it is a is a it is a preemptive protection so that it is not the assumption that you will be providing information from your notes or from your hard drive or whatever it is. The assumption going into any one of these sort of court cases that the all of the the information is protected and that it would take a very extreme need for that to be overturned. So I think it’s basically the opposite of what we have now here. You don’t you shouldn’t expect any any protections, but you may get them. Whereas when there’s a shield law in place, the expectation is that you have a privilege.

Bill Densmore: Well, it seems to me, as I’ve observed these cases over the years, that. Justice usually gets done in the sense that a lot of cases where there is a prominent. In case where this conflict arises. The judges or the judge or judges in the case find a way to navigate or thread the needle that respects the interests of the public and the lawyer who’s looking for the information. That’s usually what happens. I mean, there there are reporters, though, who’ve gone to jail for. Relatively short periods of time because they would refuse to reveal a source. And it’s important to defer that they have done that and defended that principle that we extend to. Priests and lawyers and doctors in terms of confidentiality and at least. Most people think it’s a reasonable privilege to extend to journalists as well.

Top Left Corner: Hmm. You know, one thing that I find interesting about this, this situation is that there’s something in the Catholic Church called the seal of confession. Which is the absolute duty of priests or anybody who happens to hear a confession not to disclose anything that was said. So I find it to be more than a little dose of irony in this, given that the Catholic Church sort of created the idea of of of, you know, sort of attorney client privilege, if you will.

Bill Densmore: Yeah, that’s intriguing. Intriguing observation. And also it certainly is awkward for. For the for for the church to be involved in this particular aspect of the controversy. Yeah. Because it it makes it. Uh. Seen as if the church doesn’t respect confidentiality.

Top Left Corner: Yeah, I think that.

Bill Densmore: But it’s also, on the other hand, the church is trying to defend itself and is entitled to defend itself against. Allegations that aren’t yet proved. And so it’s there’s an argument that it’s reasonable for them to start a process of discovery by asking for the kitchen sink and and acknowledge the need to narrow that scope as time goes on. And it’s a little clearer what they really need. And that’s why it seemed like the judge is gets that and is trying to manage that process of figuring out what’s really needed. And maybe at the end of the day, all the parties will agree, well, maybe we don’t really need all this stuff from Mr. Parnass as the legal reporter. And, you know, maybe there’s some way. That. That some of that information can be sourced out somehow without breaking a confidentiality.

Top Left Corner: Hmm. Well, what are the what are the potential threats that you can imagine to the ongoing journalistic investigation of the.

Bill Densmore: Well, I guess I just thinking of my own experience in journalism when I was probably really active for ten or 15 years, I would say that there were many stories I wrote where having the ability to promise somebody. Anonymity helped get a story that wouldn’t otherwise have been as rich or deep. I’m not sure. I can only offhand remember maybe one story now. Where? Which I wrote, where the promise of confidentiality was essential to being able to write the story at all. But I think a lot of times background just really helps to flesh out a story and make it meaningful and analytical and just plain more true than if you have to just go with only the public record all the time. I find actually the promise of anonymity to a source often would allow you to discover a story that needed to be written, and you could end up writing the story without having to rely on that original tip at all. But it was essential to getting the story started and a person aggrieved by that story. Might never even know how you got the tip that led you to the story.

Top Left Corner: Right.

Bill Densmore: Right. So it never comes It never comes up as an issue.

Top Left Corner: Not anything that’s going to cause a court case. Yeah.

Bill Densmore: Right. So that’s a hugely important. Feature of the feeling of being able to promise anonymity and having the source have a reasonable expectation that it’s that promise can be kept. If the source, if the court cases start going in the direction of revealing sources routinely, then that promise becomes a canard. You can’t really make that promise anymore because nobody will believe you.

Top Left Corner: That’s the threat. That’s the real danger. I know myself, I have I have started with the promise of anonymity to a source. And then later the person said, You know what? Just use my name. Just use my name. Because there’s no way that I mean, the things that I have to tell you. Only I know. And if you publish them, they’re going to know it’s me anyway. So just go ahead and use my name and let the chips fall where they may. And that, you know, that can happen too. And I always hope that the person makes that decision with full knowledge of the possible repercussions. Because I tell people, you know, if if what you tell me is going to jeopardize your your safety or your welfare, you know, just consider the possibilities seriously and solemnly. And then I had a story that I was working on in 2020 in North Adams, that required that the person that I actually have, not somebody on record, but somebody who would at least be attributed anonymously and this person wouldn’t even do that. I couldn’t write the story. I couldn’t write the story because they said they don’t even want to have a you know, they just said, here, I’m giving you all this on background. And I said, I already had that background. You know, what you have is actually very specific. And they they, for whatever reason, decided that it was too much of a threat to their job. And I couldn’t write that story. And it took me on. I’ll tell you, boy, did it take me off And I might well wait.

Bill Densmore: The terms were that they weren’t willing to even let you use the information.

Top Left Corner: Correct.

Bill Densmore: From them. Correct. I see.

Top Left Corner: So with with with the unnamed source.

Bill Densmore: I in your case, you couldn’t find another way to get that story from another source on better.

Top Left Corner: Terms. I could not and could not, not in any kind of a timely fashion. So, you know, if if you have time to work on things, sometimes you can. But if it’s a case that you’re writing something that that’s time sensitive, that anonymity. And I think that ultimately, ultimately I think that the person’s faith that. That I would go to bat for them, that I would truly keep them anonymous. I think that there was they they did not have that faith and that that saddened me because, A, it wasn’t anything that I would have gone to jail for, I mean, if I had. But B, just the idea that when I say my word is my bond, I would love people to be able to respect that. And unfortunately, I don’t think that faith in the media is as bad as the reports say it is, but it isn’t good. People’s trust in the media is not great right now in journalism. And so that might be another thing. If this if this sort of, like you said, it becomes routine to just overturn this this confidentiality, then, yeah, no one’s going to trust the the media to keep them safe. Mm hmm. Yeah. In the context of this case, the other thing that I find interesting is that you have a hugely. Powerful apparatus that is. And that is backing. This judge, judge the late Bishop Christopher J. Weldon, who is the person of interest here? They are doing this because they have the resources, They have the institutional clout to to try to force this issue. In the case of Larry Parnass, you have the eagle sort of in the in his corner in the ring, I assume. What is the what is the role that the Eagle is playing now?

Bill Densmore: I don’t I don’t have any personal knowledge of that. I think. Typically. Journalism organizations will have libel insurance that permits them to tap the libel coverage to defend a reporter who is fighting a request for confidential information. So I would suppose that’s the case with the Eagle, but I don’t know anything about that.

Top Left Corner: There’s a member of the advisory committee. Would you advise them to support Larry’s? Larry Parnass, his refusal to turn over any documents?

Bill Densmore: I would expect any news organization to do that if as a as a testament to their trust in their reporter and. The expectation that the rules were followed. I mean, there are there are many news organizations that tell their reporters, look, you can’t promise confidentiality to somebody without checking with your editor first. And so I don’t know. I have no idea. And I don’t believe it’s been discussed in an advisory board meeting. I don’t know what the policy of the Eagle is on that score.

Top Left Corner: Well, Larry certainly has a long history in journalism as well. Mm hmm. He was at the helm of the Daily Hampshire Gazette before he was at the Eagle. Brought on specifically to lead the investigative wing of their editorial staff. I think that we can trust that if there were rules to be followed, he would follow them because he’s. He’s a pro through and through. In this instance? I don’t know. What the typical and there’s probably no typical, but I don’t know what he could be looking at if he’s in contempt of court and refuses to turn over the documents. Do you have any any idea of what people have served, how many, you know, months, years or what?

Bill Densmore: Well, in the few cases where an accommodation hasn’t been reached or the request hasn’t just been dropped, I think it’s it’s typically days not not not months. I mean, you have one has the feeling that the judiciary feels that if the reporter is asked to produce something in the report or refuses, that there has to be jail time to make a make a case, to make an example of the reporter, if that’s where the judge has come down. It’s in other words, it’s it’s more. Demonstrative and punitive. And that doesn’t require long.

Top Left Corner: Yeah, I suppose. I suppose that’s the case. I guess the the one that I was thinking of that made such attention. It was back in 2005, I believe The New York Times is Judith Miller, investigative reporter for The Times that she declared. Actually, it wasn’t contempt of court that she was defying the law by refusing to divulge the name of a source. And. I don’t know how long she spent. A suitable jail. Well, I don’t. I don’t know. I should have looked this up ahead of time because it hadn’t occurred to me. But yeah. So it is not as if a a judge is necessarily going to be cowed by the clout of the organization, either if they’re run to jail near times reporters, they’re certainly willing to jail anybody.

Bill Densmore: It depends on the it would depend on the judge’s own interpretation of their role in this picture. I mean, some judges would just not want to be there. In in the position of doing that for their own personal reasons. Yeah. The opposite.

Top Left Corner: Yeah. And I suppose there has to be some weighing in of the public good of the facts of the case as well. I’m sure there are going to be a case that is potentially affects, you know, thousands of children is going to be way differently than just, some say corporate confidentiality, confidentiality laws that were breached or non-disclosure agreements that were broken. So, yeah, I guess there’s there’s going to be a lot of play. Do you think that we need in this state, at the very minimum, a shield law that presumes the the sanctity of reporter source privilege?

Bill Densmore: I when I was a practicing journalist, I was not particularly enthusiastic about shield laws because I think the minute you start to write a law in this area, then you you may create situations. Where a disclosure is required, which in negotiations with a law might not have happened. In other words, defining in precise terms the metes and bounds of what’s privileged and what isn’t. May produce more broken promises than rather than less. Hmm.

Top Left Corner: I can. I can see how that might happen. I can, indeed. Yeah. And I don’t know. You know, I know probably. You know, you said that you’re not a First Amendment specialist, and I certainly am not. But I may have to find one because I’m sure that each state has a slightly different version. And I wonder if there are any models that do find a good middle ground you could call.

Bill Densmore: I mean, I can give you offline a suggestion of someone to call.

Top Left Corner: All right. Excellent. Well, in the digital greenroom, please do. Yeah, well, we’ll be watching this soon, because I do know that Judge Judge Goodwin is going to be rendering her decision about whether or not to provide greater protection for Larry Parnass or not within the next probably few days to a week. Mm hmm. So I’ve tried to reach out to the Eagle, and they are, I think, probably talking with their lawyers as to whether or not they can speak on the issue. The answer is probably they’re not. I’m guessing. Well, it.

Bill Densmore: Would be wise. Probably not to.

Top Left Corner: Probably not. Yeah. All right. Well, Bill Densmore, again, thank you so much. It has been too long. And I will I will speak to you in the digital greenroom after we hang up. But for now, do you have any projects, any links that I should be putting in the show notes?

Bill Densmore: Not on this subject, I don’t think, no.

Top Left Corner: Does this generally generate you can put.

Bill Densmore: Put in https://itega.org/ which leads to a background on the information trust exchange governing association.

Top Left Corner: Excellent. Well, we’ll do that. And that way people can find out what you’re working on in that area. All right. And until then, have a great autumn. Thank you so much. And there it is. As Larry Pernice told me, that it’s largely in the Eagles favor. I don’t think that the elements that would have made it a complete victory are probably on the table anymore and be very challenging, at least what I assume to say to the judge, No, we’d like you to go back in there and think about this a little bit more. Judge No, I don’t I don’t think we’re going to get that. But there it is. So some sort of justice has been has been achieved. And hopefully we’ll get to talk to Larry at some point and find out just just exactly how he and the eagle feel about this, this ruling. I don’t happen to know. Oh, yes, I do. We have on our next show, episode 174, we have a special guest, Tom Conklin, who has been in radio for quite a number of years. And if he has managed to preserve one thing out of all those years in the crazy world of radio, it is a golden voice. He has just such a wonderful speaking voice and he has created his own his own business. It started being sort of a part time gig, sort of a side hustle, and now it is his main thing. He’s doing those voice overs, commercials, all sorts of reading of, you know, explaining videos, really great stuff. And it’s an interesting world because there’s more and more and more of that sort of work available. And he he tells you tells it like it is. So we’ll hear from Tom Coughlin on his voice, voice service and and who knows what else was sneak in there. Till next time, Stay safe. Be good to each other. Go easy on yourself.

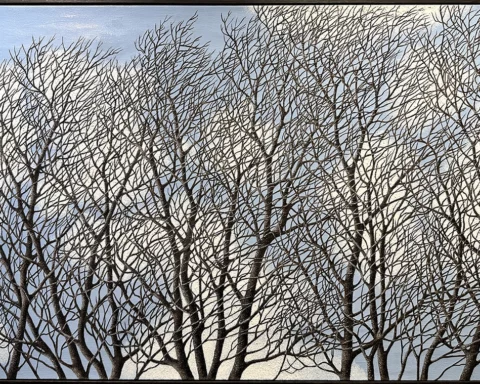

Composite image of the Berkshire Eagle building in Pittsfield, Mass. (left, photo by Joseph A. , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) and St. Michael’s Cathedral, Springfied, Mass. (photo by John Phelan, (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); collage created by Jason Velázquez, including filters to produce the effect of an ink illustration.