Podcast (top-left-corner): Play in new window | Download

LENOX, Mass. — I may be biased, but I’m pretty firmly in favor of screen actors getting strong training in a stage setting. There’s just something about the skills they absorb that makes their performances in front of the camera more vivid. And after seeing Netflix’s crazy popular dark satire/disaster film, Don’t Look Up, those biases are justified.

Oh, sure, you might say, “Yeah, but you recognized Shakespeare & Company’s Artistic Director Allyn Burrows and steadfast pillar of many a season, Company member Annette Miller, so that’s no proof.”

True, but I have not have the pleasure of seeing Aimee Doherty or Bill Mootos in a Shake & Co. production, and yet, when their characters in Don’t Look Up made appearances, however brief, I felt sure that I’d seen them somewhere, so salient is their presence.

Of course, not every actor who appears in the Tina Packer Playhouse Or Elayne P. Bernstein Theatre is steeped in Company DNA and training the way Miller and Burrows are. Still, I suspect that most performers take something special away with them after a sojourn to the Kemble Street campus in Lenox, Mass. Even the much beloved Keanu Reeves did a stint of intensive actor training under the tutelage of the late, great Dennis Krausnick in the early ’90s. Certainly didn’t seem to hurt his career.

Unless you’ve been living at the bottom of the Chicxulub crater, you probably know that Don’t Look Up, which released on Christmas Eve, 2021, and stars Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence, Meryl Streep, Cate Blanchett, Rob Morgan, Jonah Hill, and many others, posits that a meteor of “planet-killer” proportions is heading straight for Earth. The two scientists associated with its discovery find themselves on a quest to make the right people understand the importance of the extraterrestrial trajectory.

And although we aren’t likely to see the stage version of the film here in the Berkshires any time soon, disaster plot-lines actually are in Shakespeare & Company’s recent wheelhouse.

Naturally I had to get Burrows on the horn to ask him about his experiences with, and thoughts on, Don’t Look Up, the brainchild of Adam McKay and David Sirota, which is stoking the fires of America’s culture wars over things that should be solidly in realm of measurable scientific inquiry.

In addition to my conversation with Shakespeare & Company’s artistic top dog, the three other Company members who have scenes in the film generously provided some thoughtful answers to questions that came to mind as a product of that discussion. Enjoy!

GG: Perfect, couldn’t ask for better. So yeah, it’s it’s New Year’s Day and it’s it’s it’s does it feel like? Does it feel like a new year to you today?

Allyn Burrows: Yeah, it does. Because unfortunately, this weather is, you know, very foreboding, especially after doing a film like Don’t look up, right? Like. And then I read this article recently where our average temperature in the wintertime in New England is going to be seven degrees hotter as a norm. And so but two years ago, it was zero on this day. So yeah, yeah, does feel like the new day to me because, you know, it’s a sad thing as Omicron is. I mean, it’s just, you know, it’s burning through fast. And I think by March, we won’t be talking about it as much and we can get on with business and, you know, open our doors and, you know, get back to the new normal.

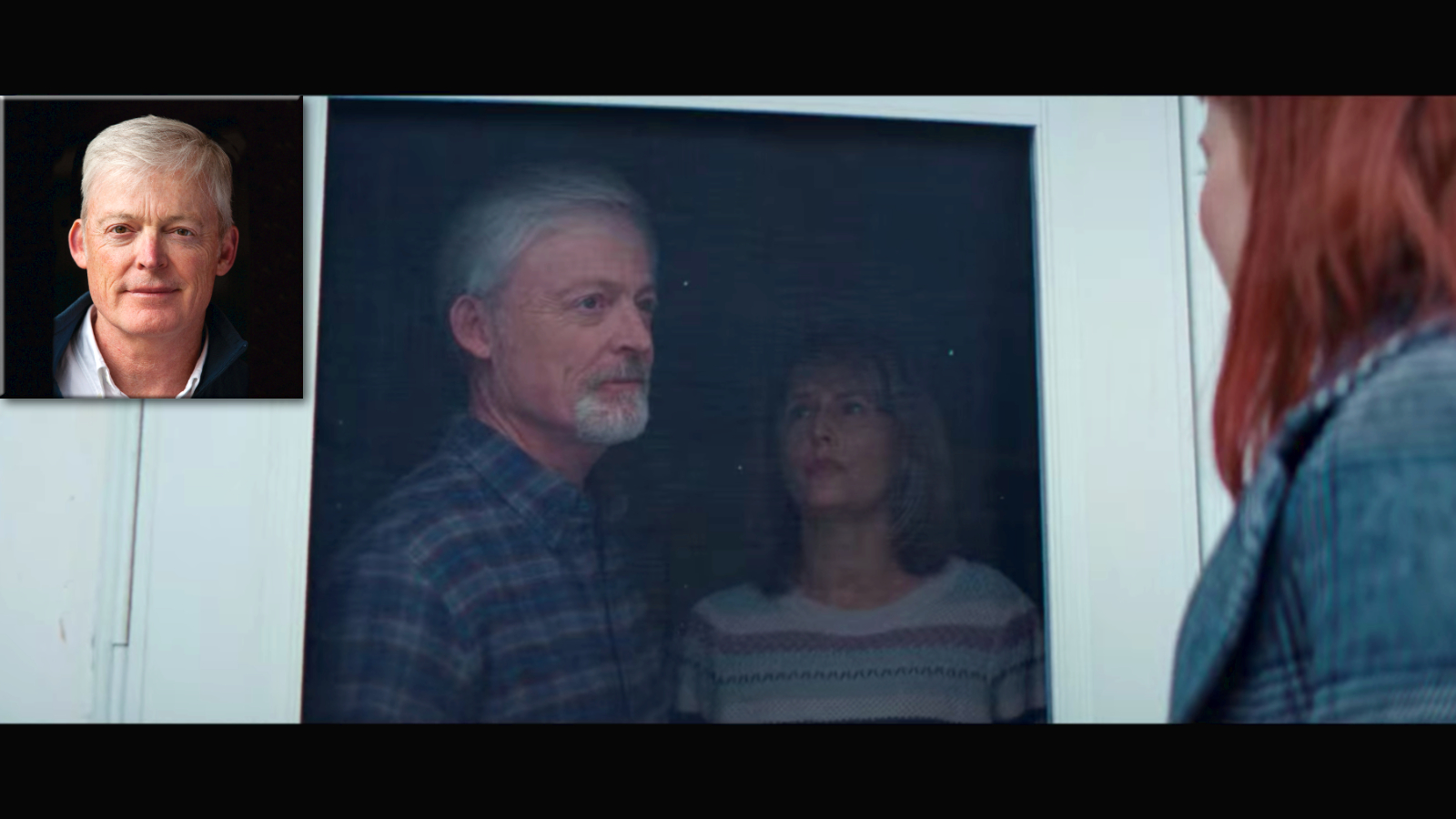

GG: I’m really hoping so. I’m I’m really hoping that every, every variant is a little bit diluted in strength. You know, I mean, I suppose you could go the other way, but I think really at this point, we cannot allow ourselves to to think that negatively. We’ve got to stay positive here. Oh yeah, which is, you know, not over yet. Yeah, we get pissed and get pissed at some very specific people and certain kinds of people. And that, to me, that to me is what don’t look up, you know, has has managed to achieve now. First of all, I want to get this out of the way up front because this was I didn’t know that you were in the film until I saw the film. Oh, okay. And then I saw your face through the screen door. Yeah. You know of the family home? Does the PhD student Kate? She goes home. She’s hoping for some, some sanctuary and her parents don’t unlock the screen door and there’s your face. Alan, I want to say I didn’t know you could glower that well.

Allyn Burrows: Oh man. Oh yeah, that’s that’s my that’s my best look right there.

GG: Oh my gosh. Yeah. Well, you know, you’ve got such a nice smile that I just didn’t just didn’t think it was possible. But no, gosh, if I came to the door as your kid and that’s the look you gave me, I’d be like, Oh shit, I’m just, I’m going to go get a motel.

Allyn Burrows: All I’m thinking is, Thank God I, I fixed that lock on the screen door. Yeah, yeah, right. You know, we had to have our little we had to have our little family contract before I opened it. Yeah, there was an extra bit where they shot. They shot me after she came in the house, right, and I looked up and down the street to make sure that no neighbors had seen her go into our house, right? And Adam McKay, the director, is like, Oh, I love that. That’s fantastic. But you know, there was a lot in that film had to cut it back. I heard, Yeah, he’s probably pretty liberal in shooting. You know, he does a lot of improvising, totally chill guy. I mean, we were shooting before vaccinations, right? I mean, right. It was crazy time. I mean, they had me quarantined in a hotel for eight days in Boston and, you know, getting tested every other day. That was even before showing up on set, you know, so right? It was. And so it was a real credit to Adam and you know, and Netflix for keeping the wheels turning because there were a lot of people on that set who who managed to be working and they were psyched, you know, and yeah, everyone’s just real pleasant. But and she was great, you know, Jennifer Lawrence just really super pleasant person and, you know, very easygoing, very laid back. You know, I I’ve been picking up these parts for years out of Boston.

Allyn Burrows: I’m from Boston originally, right? And so I’m, you know, I’m I’m on the on the radar of people like, you know, Caroline Pikmin at CP Casting and and Kyle, you know, at CP. And so and and you know, thank goodness we’ve got this mass film tax credit because that means that, you know, we’re going to keep the film industry here. And the fact that it passed permanently in the Legislature is such a bonus. I don’t know why Baker, he’s such a smart guy and I don’t know why he resisted it. It’s such a simple equation. Every dollar spent the film in the film, you know that that that production gets 25 cents back, but they have to spend a dollar to get 25 cents back. Right, right, right. I mean, for years, it’s like, Oh, it’s costing its money. There’s so many jobs created because of the film industry in Massachusetts. And, you know, I and my cohorts because I was in New York for 20 years, but I and my cohorts in Boston who grew up there, you know, we were all, you know, I don’t have any pride. You know, someone throws me a bone like that that, you know, I know I’m going to get a good paycheck for the day and I’m going to get residuals. So sure, I don’t, you know, well, I do

GG: It, you know, of course. And you know, in terms of Boston versus New York, look, I think New York gets enough screen time. I write, I mean, come on, do we have to play? Do we have to play like little sister to to the Big Apple all the time? No, Massachusetts has well, Massachusetts has some really amazing shooting locations and you know, and no location scouts really should should, you know, should take a drive around a little bit more often. So let me ask this there were actually quite a few Shakespeare and company members, you know, not the least of which was Annette Miller, who also joined you in that film. How did that happen?

Allyn Burrows: And that’s from Boston. She also knows the casting directors, you know, in Boston and they think of her, and Annette has, you know, she’s inimitable, you know? Oh yeah, that is a net. You know, she and I were also cast in a film with Ben Affleck and Chris Cooper called the company men and. And Tommy Lee Jones and. And I had to. I had some. I had a I had one just, you know, a really fun scene that I shot. It was just me and Tommy Lee Jones couple scenes and and that was in that, too. And then she played, I think, Ben Affleck’s secretary or something. But she always does a great turn in things. My wife, Mary Hickey, was also cast in this, and I was psyched because, you know, Tim gets, you know, books, a lot of stuff she used. She had a couple of her own series in Canada before moving to the state. So she is a real awesome film technician and actor. You know, she really knows how to hit her mark and her scene, unfortunately, with Meryl Streep got cut and that made me kind of sad because it would have been the first time we both appeared in a feature before. But the thing about, you know what they can depend on when these with us day players and and this is what Carolyn Pittman says of CP casting is she knows that when they roll camera and all the money that’s being spent, but per second that Boston actors, they’re going to hit their mark, you know, because four years in the 80s and the night, especially in the 80s, we were all churning out industrial films right before I went to New York.

Allyn Burrows: And and so we got we cut our teeth on, you know, make sure you hit, you know, get it on the first take baby Charlie, you’re out of there. And that makes the director happy. You know, you get one for the can. If you can get a safety on the first take, then they’re like, OK, we’re good, OK? You know, I was in a film called Manchester by the Sea that my big theme got cut out of. But Kenneth Lonergan, the director on that, he you know, there was a scene where I’m supposed to break down as this priest over these the children’s coffins. I don’t know if you’ve seen the film with Casey Affleck. It’s a great film with Michelle and and so I. You know, he came out, he goes, Oh, I got what I need. Okay, now you do whatever you need to do. Like, I’m just going to let the camera run. I thought, Oh, okay, well, then obviously I’ll, you know. And but unfortunately, my biggest scene in that got cut. So I’m pretty. I’m in that. I think it was too much to have a priest crying over three children scoffing. Maybe, you know.

GG: Well, let me ask you this. Let me ask you this about the stage actors on screen. You know, this isn’t just a blow smoke or sunshine here, but you know both you and Annette, you’re really pop on screen. What is it about your stage training that translates so effectively to the screen?

Allyn Burrows: Express, you got because, you know, you know, it’s funny. My wife and I are, she is like, she is like, cool as a cucumber when the cameras roll, but me, I’m going on stage and I, you know, I know that I’m going to feel comfortable out there, right? But when you have two cameras just inches from your face, your heart is pounding in your chest, right? Because you know that there’s so much money at stake, right? And so you don’t want to blow it. You don’t want to be that guy where they’re like, Okay, let’s try another one. Where did we get this guy right? You know what I mean? And you want to be that guy where they’re like, Whoa, okay, all right. Thank you. You know, and that comes from like like what the crossover is is making sure you’re just you’re in control of your breath because then you know that then the neck, whatever the next couple of moments are that they’re yours, right? Like I always say to actors who come in and audition for me. You know, you’ve got two minutes. They’re your two minutes. They’re not my two minutes. So, you know, take your time and just settle in and you know, you just want to make sure that you hit your mark and bring that little whatever that if it’s glowering, you know, if you read the script and you’re like, I think I think I think this is a time where I pull out my glowering look, you know what I mean? Yeah. Well, you know, those are those are the arrows in your quiver.

GG: Those are those are definitely pearls of wisdom there. I think he could go a long way by remembering to to get control of your breath. I want to talk a little bit about the the film briefly and then what it means to the arts. I mean, most people know by now that this is a film starring Leonardo Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence primarily, of course, Meryl Streep, Cate Blanchett and Jonah Hill, and a lot of great, great folks in there. Even, you know, Ariana Grande. I have a new appreciation for her, but I think that, you know, the idea that there’s a meteor coming, it is definitely going to impact with Earth. Everything is going to be wiped out, and you would think that that would be the easiest pitch to the news networks. You know, listen, we need you to understand this is a crisis. It’s happening in six months. And yet they can’t get people to take it seriously enough to actually, you know, to realize it for what it is. This is an extinction level event. Yeah. And it’s it’s an allegory. It’s satire. It’s it’s basically a I mean, most people make the connection to climate change, which is, you know, the obvious one and the one that you know, David Sirota and has talked about. But I think that there are probably other connections, you know, certainly the the the state of democracy in the United States. It does feel like there’s a meteor coming for that, too. Talk to me about when you heard the the premise of the film. Obviously, you know, it’s great to get, you know, gigs especially, you know, you know, short things that you can do that you don’t have to, you know, leave Lennox for for too long. But what about this message, did you think was worth telling?

Allyn Burrows: Oh, well, you know, you hear very, very little of the story oftentimes, right, like they I don’t know if I got a whole script in advance. I just heard, you know, you get the storyline and you get a chunk of change pages and you get your your daily sides and then and it’s like, OK. And then you have to draw your own conclusions, right? And that’s kind of where I went. I was like, Oh, OK, so it’s the destruction of the Earth. You know, it’s not the first time we’ve seen a destruction of the Earth movie, right? It’s the way he tells it. That is so on. So ground level and so kind of folksy, you know, and the way that the actors were having so much fun and so much of that is just kind of he puts an ironic spin on it. I mean, the fact that Cate Blanchett plays that role, I mean, like, he really fills out the characters and brings this level of humanity. And and then and then you’re like, Oh, I see it’s not just a meteorite heading towards the Earth, it’s humanity. All this fun we’re having is also going to get wiped out, right? I don’t know if you’ve seen the show station 11. Yeah, I’m watching it now. It is. It’s basically when a pandemic wipes out most of the population on Earth, and it’s the survivors. And, you know, and it tells the moment that it’s happening when people are like, when all the flights are being cancelled and it bounces back and forth in time.

Allyn Burrows: I’m watching because there’s no more gas, of course. So the Shakespeare troupe is having their their ARVs pulled around this tour circuit by horses, and they do Shakespeare plays to all the Bedouins who remain right. And so, you know, I mean, why they would choose, you know, like Shakespeare survives. That’s funny. It’s really it’s really morose. Like friends of mine watches like, yeah, I watch 15 minutes of it. I couldn’t. I couldn’t do it. I’ll never think about it. It’s Station 11. Yeah, there’s nothing grotesque about it. It’s just so like, it’s like, Yeah, you know, there’s no more humanity. So I mean, at the end of the day, I don’t want to sound too existential or anything. But yeah, meteorite hits the Earth and the Earth gets blown up. Boo hoo for us, right? You know, and I think humanity always makes the mistake of thinking that, you know, that we’re the most important thing on Earth or were the most important thing to existence in general right now, we’re the most important thing to ourselves. Sure. But in the meantime, you know, why not try to convince people that at least something is happening like a meteorite? I mean, the fact that he couldn’t even, you know, Leonardo, to his credit, you know, and he’s not the improviser that you know, someone like Meryl Streep is or Jonas Hill, you know, so they’d be on set improvising.

Allyn Burrows: And you know, he he’s he’s a long time film actor on this is a warm up through the comedy starring Meryl Streep as a stage actor. They’re used to being like, Yeah, roll camera. I don’t care. I’m a star. I can burn as much film as I want, so they’re going to like, you know, and they’re encouraged by the director. But Leonardo, he has his process, and he’s had his process since Gilbert Grape. Right, right. Very defined. And he’s a very serious artist. But it, you know, it’s I don’t know, has he ever done a stage play? I don’t, you know? So, yeah, so interesting. The message is. Huh? The message is, you know, you can kind of take it or leave it and other people. I mean, I have friends who, you know, don’t have the same politics that I do. You can probably guess what mine are. But, you know, but they still are like, Wow, that was quite a message on the pandemic. And I’m like, What’s really about the pandemic, dude? You know what I mean? It wasn’t about this wasn’t about the country being divided. Exactly. It was about the extinction of all humanity. Unless we get our shit together, you know, like, Oh yeah, I guess so.

GG: Well, you know, what’s the parallelism? The parallelism between, you know, you know, DiCaprio is is playing Dr. Randall Mindy and Lawrence is playing PhD candidate Kate DiBiase, and they are trying to convince everybody of how important this is. There is a desperation in their characters behavior that mimics or parallels the desperation in this film’s attempt to get people to understand the seriousness of the situation. It almost seems like it is. It is a one to one ratio between the characters really fevered a fevered pitch. And Adam McKay’s fevered pitch to get people to understand because, you know, you know, there are all of these. We have 12 years not to to cross this, this temperature threshold. Well, fuck it, we missed it. Oh shit. Yeah. Now what? Yeah. So I think that, you know, the the producers of this film have taken some grief, at least in the online, you know, intelligentsia on the right and even some in the middle about how it’s it’s such

Allyn Burrows: It’s so true. You just say intelligentsia on the right.

GG: And I know it’s a contradiction in terms.

Allyn Burrows: Sorry.

GG: Yeah. You know, but what passes? What passes for that? Ok. Right? Yeah. So the the best they can, the best they can bring anyway. But the the idea here is that you’ve you’ve got people responding to this film in the same way that the characters respond to the news of the media. And they are. They’re saying this is melodramatic. You get people all worked up, and, you know, it’s it’s not it’s just not something that that she should be, you know, getting the public wound up about. But this is the arts. Is this not what the arts does? I mean, whether it’s, you know, visual art, you know, such as, you know, Picasso’s various sort of anti-war paintings or whether it’s yeah, or whether it’s Shakespeare who, you know, used his own literally his own theater to to poke and jab where he felt it was due.

Allyn Burrows: Yeah, well, he was also on the, you know, he was on the payroll of the king, right, too, right?

GG: So, so he poked gently. Yes.

Allyn Burrows: Yeah. You know, and everyone likes to think that they know knew what Shakespeare was thinking. And and and I mean, I argue about it with people all the time, you know, it’s like, Well, that’s even people say, Well, that’s not what the text says. And I’m like, Wow, that’s that’s what you says. You know, that’s where you like the text to say, so everything is subjective. I thought Adam McKay or. And the producers were really brilliant in how strategic they were. I mean, I’ve heard from, you know, I’ve had I’ve had small roles in feature films before. I’ve never gotten the kind of surprise from friends of mine all over the place where, like I, I spit my beer out when I saw you the other night, you know, and it’s like, Yeah, I know. You know, this is what it’s kind of what I’ve been doing for all these years, off and on and and the way they presented it right from the get go, that kind of visual assault with the titles, really, you know, bright orange, you know, and and they they timed it at a time that everyone would be kind of they did they know that Omicron would shut everyone in? Did we know? But they timed it for the right at the holidays when they might have speculated that a lot of people would see it? I think that it also is a pretty easy pill to swallow for people who may or may not want to subscribe to what the film is saying, right? It’s like they can. It’s like, Oh yeah, it’s a satire. It’s it’s satire that you know, actually, you know, could really land in the realm of reality. I mean, meteor meteorites are flying around all the time. This one was, what, five six kilometres wide. And that was a I didn’t, you know, that may be a fact. I didn’t know that I was like, really? If a if a if a meteor hits the Earth at six kilometres wide, that’s an Earth ending event. Oh yeah.

GG: Oh yeah, they yeah, you know, they’re coming in so fast. The impact is so hard. What I only found out recently there was a fellow who was actually an astrophysicist who wrote about what actually would happen if this this occurred and the the effects are surprising in that one of the things that happens is that lots of debris from Earth shoots up into space. It bounces, basically bounces. And then you have a couple of days of of of hot, molten lava raining down through the atmosphere. I’m like, Wow. So this is it’s even worse than the movies portray.

Allyn Burrows: Yeah. Yeah. So that was the Big Bang, right? I mean, right? We have no dinosaurs because something hit the Earth and then the sun was over cloud and all the vegetation died. So, you know. Well, let

GG: Me talk

Allyn Burrows: About, I think, what will happen to people. Yeah. No. Go ahead. No, I was going to say, what? You know what really gets? You know it all the all the destruction happened in an instant in this film, so that made it kind of palatable to what what’s really going to happen is, you know, if something you know, an earth shattering event is the way people will ultimately go into survival mode, and then that’s going to get really, you know, it could get really drawn out and gross, you

GG: Know, yeah, you know, people will survive. And what kind of a world could they possibly inherit? Let me ask you this. I mean, this is kind of and this is really sort of the. The jewel in the crown of this conversation for me, because I know that there’s a lot of convincing that needs to happen about a number of topics. Certainly, climate is a big one, but you know, there are other other, you know, some dire situations out there in this world. You have an immense amount of power as the artistic director of Shakespeare and company to affect what people are thinking about, who come to the who come to sit and take in the shows that you you produce. What kind of decisions do you think you can make going forward to? To be a part of the conversation, to be somebody who moves the needle. You know, however much you can in the time that you’ve got them, whether it’s 90 minutes or whatnot, what kind of thought goes into your decisions on what you put on those stages?

Allyn Burrows: Well, I mean, you really have to navigate everything, right? You know, right now we are also at an inflection point when when it comes to society. And so, you know, we the last several years have been looking at everything through an inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility lens. And we and and that is kind of where we start. How do we access these stories and how do we, you know, have them reach the people who are going to come and take them in? And what are we going to say? I used to say. You know, people have to feel shifted when they leave. One of our productions, they have to feel they have to feel a measure of diversion. They have to feel a measure of, you know, satisfaction. But they also have to feel slightly different. That’s what a good story does. It draws you in. And once you draw someone in, you have the responsibility, as you know, a member of society to do the right thing by the material and the people who have come and rented those seats. So I’m not into kind of I used to say I don’t want someone to leave the theater. And then just first thing they say is, where’s my car? Right? I want them to say, I want them to come out and be like, Wow, whoa, whoa.

Allyn Burrows: I got a I got to sit for a minute, you know, or whatever. And you know, we have to do it in a way. If people are coming that we, we that we really we do it in a way that people kind of get drawn in. And then once we have them, we’re having larger conversations. We’re having conversations of import, we’re having conversations that, you know, they may be funny. A lot of you know, because there’s nothing like comedy to cut through the bullshit, you know, but but they also, you know, they have to they have to be meaningful because people are spending good money, they’re spending good time time. It’s just as valuable as money. We’re spending a hell of a lot of time putting them on. So at the end of the day, they have to be substantive. They have to be something that counts and has impact and import. So, you know, people will pitch a show and I’ll be like, OK, great. Do you think it’s a good play? Yeah. Well, we should do it for this reason. I’m like, Well, let’s just find out. Let’s just start with whether it’s good play. Sure. You know, and a good play is whether people are really kind of moved by it in any number of ways, whether they’re, you know, they’re really have a good time or they really are, you know, kind of turned upside down by it or whether they they they they go away and they have to think about, you know, the larger issues that confront them in life.

Allyn Burrows: And so, you know, that’s kind of what I’ve always I mean, this is my I’m going into my 15th year as an artistic director, right? So I mean, I’ve been here for five, but I was in Boston at another company for nearly 10. So this all comes out of conversation before we do a show. And then it’s all about the education. Four of the kids, you know, how are we, how are we having them experience Shakespeare and his his great poetry? And you know, you know, again, he was a white male playwright. So you have to take all these considerations in and we train people and how to tell these stories as well. So it’s a really long winded answer to saying you’ve got to do the right thing. No, I hear you and your audience and your artists and and and. And it can’t suck.

GG: Yeah, yeah, no, obviously you can have you can be telling a great message. But if the if the material is is, you know, subpar, that message is never going to get anywhere. I mean, I think you’re you’re your your note about comedy being a great way to sort of cut through. I guess it was. I think it was Annette Miller a couple of years ago when the Waverly Gallery, it was a story about dementia or Alzheimer’s. And you know, if you have somebody in your family, as I do with Alzheimer’s, you can laugh because you have to. And there’s some genuinely funny things that happened. But it’s also, you know, it’s also, you know, just gut wrenching every step of the way. So that was that was a really a good a good story, a good, good, you know, theme. Hey, Alan, what what do we have?

Allyn Burrows: My dad had Alzheimer’s, and I used to joke that, you know, I’d love. I used to love to run lines with him because he never got bored of it. By the time we got to the last page he was, he would turn it over and be like, What are we here? Writing We have here? All right, let’s do it again. No one really wants to run lines with you.

GG: Yeah, but let’s talk about let’s talk about twenty twenty two since we are officially in 2020. I’m going to be writing, you know, sending my checks twenty two and one for a while. But still, yeah, yeah. It’s it’s usually a little too early on on January 1st to know what’s coming up. Do you have anything picked out for this season yet?

Allyn Burrows: Yeah, yeah, no. We’ve announced our Shakespeares and and one and another classic piece, which is an Iliad and Makani, a chesser who’s a company man who’s gonna play Lear with Christopher Lloyd last summer. She did it over at the Anchorage Opera House in the fall, and she only got to do eight performances of it. It’s a one person play. And, you know, it’s about the Trojan War. Yeah, and he plays a poet. It’s just a very impactful piece, and she’s just awesome in it, and I went and saw her in it. And, you know, I want to revive that. Have the director who directed it over there, Jeff Russo directed for us, and that will be in the Packer Playhouse and then also measure for measure, which is a play we haven’t done really ever on our main stage. They call it a problem play. It’s a great play. We get it in the stables in 1996. Last, as one of our big productions, we took it to Boston and and we did a workshop production of it last summer kind of ran it up the flagpole and I thought, You know what? This deserves a fuller production and really to be fleshed out, and Alice Regan will direct that. And then, you know, we were slated to do Lear in rep with much ado about nothing on the new spruce, but it got really complicated to do to with all the COVID restrictions. So we’re going to bring that out under the new Spruce Much Ado for the summer. And Kelly Galvin, who’s directed a bunch for us, will direct that and we haven’t done that since. On the main stage since 2003, when I played Benedict. So, yeah, so 18 years, that’s long enough to wait to do much ado about nothing.

GG: I would say so. No, this sounds like you’re really exciting season shaping up there.

Allyn Burrows: When? Yeah, and then and then we’ll we’ll pick some modern titles again to exactly kind of what you were talking about, how can they have, how can they have punch and and and really leave someone with something?

GG: All right. Well, as as always, we we asked folks where they can find out more information, and the answer is always really simple with you because it’s just Shakespeare, dawg. Some smart individual back in the beginning of the internet decided to snag that URL and by gum, that was the smart thing. So Shakespeare Dawg keep and of course, you’ve got a newsletter that people can sign up for so they can find out all the information as soon as it becomes available. Alan, I want to say thanks so much for speaking with the top left corner again.

Allyn Burrows: It’s great to hear you, Jason, and happy New Year to you.

GG: Thanks. Thanks. You too.

Allyn Burrows: Let’s all get together and make it a good one.

GG: Amen to that. Talk to you soon.

Allyn Burrows: Take care. All right. Take care. Bye bye.

GG ~ Do you personally feel that “Don’t Look Up” hits the mark as far as getting its message out?

Annette Miller ~ I was thrilled to be cast in Don’t Look Up, and have the opportunity of working with Adam McKay and his entire team on this very relevant film — a satire on our society that refuses to “look up.”

Adam McKay has used satire as the means of telling this important story of Don’t Look Up. We are a world burying our heads in the sand.

GG ~ What do you try to bring from your stage training to work in film, and can you feel it when that training is serving you well?

Annette Miller ~ In terms of your questions, what my stage training brought to my film acting: Playing a role on stage or film, you ask yourself the same questions about your character in the scene:

- “What are you doing?”

- “Why are you doing it?”

- “What do you need from the other people in the scene?”

Annette Miller ~ I always say — the simple formula 4w/how. That is, who you are, what you want, when you want it, why you want it. All of that determines how you go about it. All of those are the same intellectual questions you ask yourself on stage or film. The actor, though, has to use those questions to ignite their emotional and sensory receptors to the particular moment in time and space.

The main difference is that the actor doesn’t have to project his voice to the 3rd balcony on film so in that sense it is a more intimate art form.

GG: Is the world of the Arts doing enough these days to fulfill its traditional role of societal/cultural mirror and critic? How might the Arts better take on some of the challenges and crises humanity faces today?

Annette Miller ~ YES, THE ARTS continue to mirror society. An artist always expresses today’s world in his/her art form Hopefully, not Didactically.

Become a patron of (and subscribe to) the show on your favorite platform!

GG: What do you try to bring from your stage training to work in film, and can you feel it when that training is serving you well?

Aimee Doherty: I think the part of my stage training that served me best was preparedness. Learning all the lines for Rosalind in As You Like It takes months of preparedness ahead of time so you can hit the ground running when the cast begins rehearsals. When shooting a movie, there are hundreds of people on set. You need to know what you are doing and have your lines down before you show up to set because the director usually doesn’t have time to work with you individually. You are a small part of a very large and expensive machine and you want to jump in and keep it moving.

GG: Is the world of the Arts doing enough these days to fulfill its traditional role of societal/cultural mirror and critic? How might the Arts better take on some of the challenges and crises humanity faces today?

Aimee Doherty: It’s a difficult balance. Do I think the arts can do more? Yes, definitely. The question is will anyone watch it? Funding for the arts is scarce, so many times art makers, who usually operate on razor-thin margins, choose projects that will appeal to the masses so they can stay out of the red. I think if funding was increased we would see some revolutionary work.

GG: Do you personally feel that “Don’t Look Up” hits the mark as far as getting its message out?

Aimee Doherty: I worked for a dozen years as a Senior Scientist at an environmental engineering firm prior to acting, I think this film is right on the money. The corporate greed that is steering out environmental laws behind the scenes will be our downfall.

GG: What do you try to bring from your stage training to work in film, and can you feel it when that training is serving you well?

Bill Mootos: I think the essence of acting is being truthful, and that applies to both stage and film. Good acting training involves being truthful to the character you portray and the circumstances you find yourself in, and I think keeping those things at the forefront will always make for a better performance. There are technical differences in how you approach each medium, but being true to the moment is essential in both.

GG: Is the world of the Arts doing enough these days to fulfill its traditional role of societal/cultural mirror and critic? How might the Arts better take on some of the challenges and crises humanity faces today?

Bill Mootos: The goal of the arts to me is to continue to hold that mirror up to the world so we can see ourselves, flaws and all, and work to make the world a better place. People also want to be entertained, often to the point of completely forgetting about what is wrong with the country or the world. This places “the Arts” in a tough position, because for many the need to be entertained outweighs the desire for enlightenment. So we have to walk a line between appealing to what people think they want and our need to tackle important issues. As to how to better take on these challenges and crises, I think that is always the dilemma. It is finding good, relevant, worthy projects that can entertain but also make us think and feel, and inspire us to act. For me, that is always in the writing. We need to constantly seek out the best writing and prioritize that work as opposed to just going for what we think will offend the least or entertain the most.

GG: Do you personally feel that “Don’t Look Up” hits the mark as far as getting its message out?

Bill Mootos: What I have noticed about “Don’t Look Up” is that it has triggered more online conversations than any project I have ever been involved in. Audiences and critics have wildly different opinions about its content and its message, and they are very eager to voice their thoughts. So in that regard, I think it has already hit the intended mark because it has inspired so many thoughts and conversations. I think for many of us it really hit home in terms of how our country reacts to existential crises, and how almost every important issues devolves into a political battle. It’s hard to really laugh at what we have already seen playing out so horrifically in our local and national governments.

— END —

You must be logged in to post a comment.