Like so many privacy advocates, I cheered as Apple, Inc. unzipped and laid its set of big brass corporate disobedience on the table last week. Despite some convincing analysis both on Medium and over at Slate.com to the effect that an iPhone used by Syed Rizwan Farook, a shooter in the 2015 San Bernardino massacre, probably contains no useful evidence, the Federal Bureau of Investigations insists that Apple create access for investigators to the phone’s contents.

In its open letter to customers, Apple delineated its rationale for refusing to comply with a court order, issued by federal magistrate Sheri Pym, instructing the Cupertino firm to engineer a back door into iOS. The main thrust of their argument is that to create and deploy such a software vulnerability once is to jeopardize personal, corporate, and governmental information security forevermore. Apple CEO Tim Cook warns that once you release the type of hack being requested by the FBI into the wild, no one will be able to lock it back up in Pandora’s Box again.

Social media was on fire all week, with an apparent majority of netizens weighing in on the side of Apple. One tweet that was quoted frequently lamented at the inverted nature of data-privacy where corporations had to protect the public from government intrusion instead of the other way around. After reading that for perhaps the third time, I felt a growing unease begin to creep into my thoughts. Because of the undeniable logic of Apple’s missive, however, I simply could not put my finger on what was so troubling about the sentiment.

DOJ doesn’t wait for deadline to pass before flexing its muscle

This past Friday, news broke that the United States Department of Justice had filed a motion to compel Apple to write the malware that would circumvent a critical iOS security feature. The safeguard was designed to shut down, and wipe the data from, a phone whose security code had been incorrectly entered too many times in a row. Here’s the interesting thing: the DOJ didn’t wait until Apple breached the February 26 deadline set by the court order before filing its motion to compel Apple to do its bidding.

My apprehensions began to swirl as I attempted to fathom the Justice Department’s strategy and divine its ultimate goals. The shooting happened almost three months ago. Both Farook and his wife destroyed their personal cell phones, leaving only the phone issued to Farook by his employer. The shooters took their own lives, we are told, rather than face capture. What information do investigators think they’ll find on that phone that would be likely to thwart a future terrorist attack?

And then, as so often happens, a seemingly unrelated piece of news helped bring the facts into focus. The DOJ would go Beast Mode over this issue even if the only data likely to reside on the device ends up being a note to pick up some hummus on the way home.

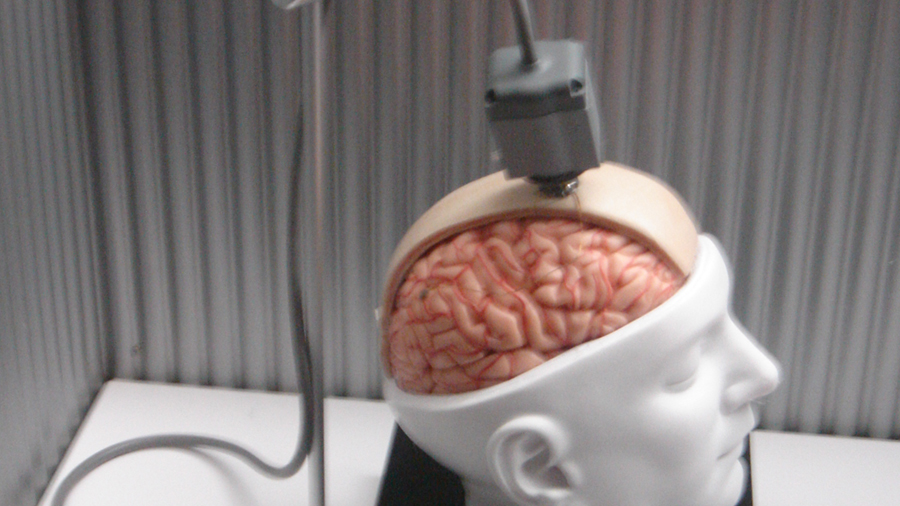

DARPA announces push to accelerate neural-computer interface

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) announced on January 19 that it is working to bring the capabilities of the “Matrix” within reach. The Neural Engineering System Design (NESD) program aims to develop an implantable neural interface able to provide unprecedented signal resolution and data-transfer bandwidth between the human brain and the digital world.

With a projected budget for the NESD program of $60 million over four years (a steal, really, if they can pull it off), DARPA suggests that potential applications are devices that could compensate for deficits in sight or hearing by feeding digital auditory or visual information into the brain at a resolution and experiential quality far higher than is possible with current technology.

Failing that, of course, the military may settle for unstoppable Terminator units controlled remotely by 17-year-olds from an undisclosed hotel room outside of Las Vegas.

Seriously, I’m excited by the medical implications. And I’m actually not too distraught over the killer cyborgs. If the human race could shrink war to a hopped-up, ultra-tech version of Robot Wars, the planet would thank us.

Here’s the thing though — Phillip Alvelda, the NESD program manager, says that “Today’s best brain-computer interface systems are like two supercomputers trying to talk to each other using an old 300-baud modem…Imagine what will become possible when we upgrade our tools to really open the channel between the human brain and modern electronics.”

Yes. Let’s all imagine that for a moment.

Google the phrase, “neural computer interface,” if your imagination is inadequate. And then fast forward a couple decades to a time when consumers look forward to the day, perhaps our 21st birthdays, when we can legally have a device, perhaps no bigger than a thin dime, embedded in our craniums. This implant would probably be a wireless device that could process terabytes of information per minute, either to store in an auxiliary drive in your head or upload to the cloud.

Dead men’s phones tell tales, and so might live implants…

Someone’s going to have to build that device. Someone’s going to have to write that OS. And the data security issues that arise when this scenario comes to pass (maybe in 20 years, maybe in 10) are going to make the U.S. v. Apple 2016 throw-down look like an argument over playground kickball rules.

Because the missing ingredient in the San Bernardino case is this: a live defendant. With both Farook and his wife dead, the entire question of access to the information on the iPhone assumes that the only two interested parties are the corporate entity that produced the phone and the government, which is relying on the All Writs Act of 1789, which says, basically, that the government can order people and organizations to do whatever the hell it wants, if justification can be based, however thinly, in existing law.

Completely and conveniently removed from the equation is the private citizen to whom the information could be said to belong in the first place. Now the only matters to be decided are whether or not Apple is technically competent enough to comply with the motion to compel and, if so, whether the DOJ has the authority to back up the FBI’s position. The debate is about technology, rather than about Fourth Amendment (protection against unwarranted search and seizure) or Fifth Amendment (protection against being forced to supply evidence against oneself) implications.

If Farook were to have lived, I have little doubt that a court would be justified in ordering him to unlock his phone. And he would have the right to appeal. Upon losing the appeal, he might choose to rot in solitary confinement or face the death penalty rather than comply with such an order, but the discussion would at least include some constitutional considerations.

Attempts to simplify and frame the conflict as a pissing contest between the federal government (which fewer and fewer people trust) and Apple, Inc. (which the public kinda-sorta trusts) are lazy, misleading, and reckless. A power-play concerning data access is totally in the offing, but it’s going to be between the governments of all nations and their 8 billion citizens.

Justice Louis D. Brandeis, in the dissenting opinion in Olmstead v. United States (1928), wrote, “Discovery and invention have made it possible for the Government, by means far more effective than stretching upon the rack, to obtain disclosure in court of what is whispered in the closet.”

Or whispered in the mind, perhaps? People with smartphones typically go nowhere without them. I suspect that the convenience of having all the features of a smartphone without an actual phone would be hard to resist. What happens if DARPA succeeds, as I hope they do, in creating an implant by which I could access the sum of all human knowledge with a thought? Or order a pizza merely by imagining roasted red peppers, black olives, and extra cheese? Or having the nastiest, kinkiest, sloppiest sex with my darling wife from 400 miles away while I’m on a business trip and have it seem as real and steamy as analog?

And then replay that skin session from flash memory the next night as she’s watching the 15th season premiere of “House of Cards?”

Aye, there’s the rub. Right now, the thought locked securely in the mind is sacrosanct. Although torture is still employed during interrogations both at home and abroad regardless of the efficacy of the technique, the privacy of the mind has long been revered. That the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1963 that confessions extracted as a result of administration of truth serum were “unconstitutionally coerced,” and therefore inadmissible, suggests limits beyond which authority may not go to compel access to the wetware in our skulls.

Presently, I can think as many deviant, despicable, dangerous thoughts as I like. Once those thoughts migrate out of my head, however, and onto a physical storage medium, my expectation of First, Fourth, and Fifth Amendment protections degrade rather quickly as my privacy becomes vulnerable to the interests of society. My mobile device, laptop, or even onboard computer in my car can be hacked and inspected for proof and details of criminal activity.

Privacy implications of an Apple loss

But what if my mobile device is a tiny chip, manufactured by Apple (let’s call it the iLobe) that has an operating system with a built in “back door?” Unfortunately, Apple lost it’s appeal against the DOJ back in 2018 because its defense rested on principals of corporate law and technology rather than on constitutionally guaranteed civil liberties. Because of this engineered security hole, no torture, no truth serum, no intimidation of any kind are necessary to mine the data in our brains. Our “always on” wireless connection is sending all our ideas, benign or evil, to the Cloud for backup.

Who would you trust with unfettered access to your every thought? As long as the U.S. v. Apple 2016 controversy continues to be molded into a version of reality where either Government or Business are allowed custody and control over our personal information, but never the people, the Privacy of the Mind will never even be a subject of discussion.

Of course Apple wants to see terrorists (or mentally unstable health department employees) stopped before perpetrating bloodshed and quickly apprehended if violence has already occurred. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t. Tim Cook is in a unique position to know, however, of the peril inherent in what the FBI is asking of the company. But while Apple is right to oppose the court order and motion to compel — and base its defense on stated objections — the rest of the public should not assume that this fight should be Apple’s alone. Does Apple really care about the personal privacy of its customers? Probably. But the public has its own interests at stake and should never expect any corporation to act as champion for our privacy. Even the ACLU got it wrong when it issued its statement on the situation February 17, falling into the same corporate rights trap from which there is little hope of escape once ensnared.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), which is sometimes at odds with Apple’s policies, issued an appropriate statement of support of Apple’s position, centered squarely on security and privacy concerns. This fact is in no way surprising. I’ve always liked the notion of looking ahead to steer away from hazards to our liberty that may crest the horizon, safeguarding the frontier. I believe that the more democratic framers of the constitution may also have had that thought in mind when they settled on the Ninth Amendment:

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Scholars may argue over how much protection is afforded by a person’s “right to privacy” or whether or not such a right even exists. My instinct is that we all know when ours has been violated. I have no doubt that purely scientific curiosity will generate “Discovery and Invention” that open up windows into information locked in the mind, the body, and perhaps even the spirit. Let’s make sure in the early years of the 21st Century that we assign dominion of the realm of human thought to the individual, rather than some centralized agency or corporation. Write letters. Talk about the issue at the pub and around the water cooler. Make pacts with friends and family to protect the sanctity of the internal secrets of your tribe — holiday gatherings are rough enough without worrying that your every impulse might end up on the Internet after a malicious hack. Right? I mean, your cousin’s hot. You’ve thought about it, you know you have. How many people should have access to that whimsy?

For now, I think we should definitely applaud Apple for making good on a promise they made 33 years ago.

This article appeared first at Medium on February 21, 2016

You must be logged in to post a comment.