It never fails: If I see a piano without a sign that specifically says not to play it, I play it. Not for more than a few seconds. Not more than a quick dash over the keys. Usually it’s a bit of Chopin or Clementi. I keep it light. No one likes the attention seeker who sits down and plays an entire recital. For me, it’s something that I just need to do, while standing, for a few seconds.

On the occasions I find myself alone with a piano, though, that is when I slow down and take my time. That is when I sit. I adjust the bench or chair. I check my placement and my posture. And only when I’m completely ready, I launch into Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C♯ Minor: a piece that has seeped into my being more than any other. My senior recital piece. The piece that I think of when people ask for a classical music recommendation. The piece I shed more tears over while learning and that made me work harder than quite possibly anything else in my life.

I recently spent nearly a week in the Finger Lakes wine region (FLX). While there, I found myself listening to the Prelude on my drives between appointments. I found myself humming it mindlessly as I wrote my reflective notes at the end of the day. It was stuck in my head as I tasted. The story—and experience—of Finger Lakes wine is no more perfectly analogized than with a nearly note-by-note match to the Prelude. Over the three parts of this dive into Finger Lakes wine we’ll get to know the terroir of the region, meet the families (and delve into their unique philosophies) behind its distinct personality, and inspire your #winecountryweekend in what absolutely deserves its title: the best US wine region for two years running. If you wish to listen along, I recommend this version of the piece, played by the composer himself from start to 1:47 (if Spotify isn’t your thing, a version by Rousseau, can be found on YouTube.

The First Movement: Glacier, Lakes, Grapes

The Prelude opens with the deliberate striking of three descending chords, dramatically setting the stage. The Finger Lakes also began with three deliberate strikes that created what has become a wine region on the world stage: glacier, lakes and grapes.

Pleistocene Age Glaciers

For most of its not-so-distant pre-history, New York State was covered in two-mile thick glaciers that advanced and retreated episodically. The most recent movement occurred about 21,000 years ago. Two thousand years later the climate warmed, melting the glaciers and leaving eleven long, skinny lakes in the shale and forming steep slopes of sediment over a period of about eight thousand years.

Eleven Lakes That Moderate A Cool Climate

When people familiar with New York State think of the Finger Lakes region they often dismiss the idea of wine because the region is known for its bitterly cold winters. However, the length, width and depth of the lakes created a region that, while known for being cold, actually has a unique micro climate.

In wine, there are two categories of climate regions. Warm climate wine regions see more consistent temperatures throughout the year and are located close to the Equator. There is far less of a drop in temps as summer becomes Autumn (think San Francisco!). This lowers the risk for frost but means that the grapes often lose acidity.

Cool climate wines are further from the Equator and see a significant change in temperature from summer to winter. This poses greater risks for frost and can lead to years where grapes cannot ripen enough. However it also means the wines retain delightful acidity. While people may not think of it regularly, many of the world’s best wines come from cool climates. These areas may be warmer on average than the Finger Lakes, but the lakes do their magic allowing these small pockets to flourish.

In addition to the water, the aggressive formation of the lakes left steep slopes allowing for great drainage and access to sun.

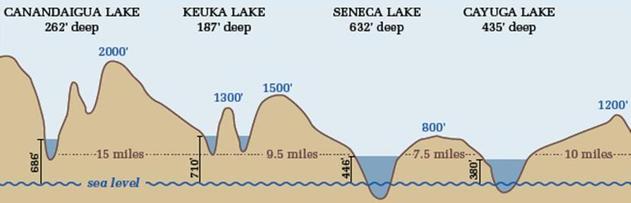

The long skinny lakes of the regions aren’t just eponymous, they also create the perfect cool-climate wine region. Because they are narrow and deep, and water changes temperature much more slowly than the areas around it, the vineyards are often spared an abrupt change in temps. This moderation of temperature keeps the region warmer than the rest of western NY in the winter and cooler in the summer.

In addition to the moderating effect, there is a Banana Belt—the southeastern shore of Seneca lake—which is so warm you’ll find Cabernet Sauvignon growing there. It is not, however, a warm climate.

Seneca and Cayuga lakes are two of the deepest lakes on the continent and are below sea level at their deepest points.

Versatile Climate, Varied Grapes

The naturally cool—but moderate—climate and Banana Belt allow for a vast variety of grapes in the region. Winemakers in the region embrace all grapes be they vinifera, hybrid, or native. And while I hate to beat a dead horse, notice how everything comes in threes, just like the first movement of the Prelude.

Vinifera

Chardonnay

Gewürzt

Riesling

Pinot Noir

Cabernet Franc

Lemberger (Blaufränkisch)

Cabernet Sauvignon

Syrah

Pinot Gris

Grüner Veltliner

Muscato

Rkatsiteli

Saperavi

Hybrid

Vignoles

Cayuga

Vincent

Native

Niagara

Catawba

Concord

While not a definitive list, it’s easy to see the incredible versatility found in Finger Lakes grapes and the wine reflects this not only in varietal but also the many winemaker choices. The second part of this series moves into the frenetic pace of the second movement to explore the people, philosophy and economy of the region and how those have taken this wine region to the next level.