Editor’s Note: This exhibit closes March 31, 2019.

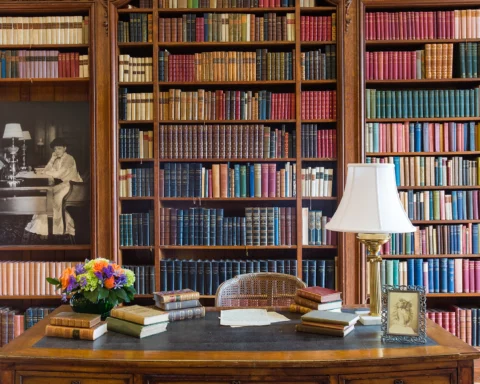

After arriving at Bennington campus through wrought iron gates, you ascend a meandering road until you reach the crest of a hill. Before you is a behemoth of a building—a 1000,000 square foot cathedral of wooden high beams and glass, dedicated to creating something from nothing in visual art, dance, and performance. This is VAPA (visual and performing arts) Center, situated on a summit against the surrounding vistas of the Green Mountains. Visitors enter by climbing the industrial stairs to the Usdan Gallery. It was modeled on the 3rd floor of the Whitney Museum when the museum was on the Upper East Side of New York, now the Met Breuer. Like the building, the gallery is mammoth. Constructed 40 years ago with the spirit of mid-century large scale color field paintings and minimalist sculptors such as Helen Frankenthaler, Jules Olitzki, and Anthony Caro, who were students and faculty at the college.

This is a difficult space to curate an intimate exhibit of small works. Somehow the curators, Anne Thompson, director of the Usdan Gallery, and faculty member, Josh Blackwell have successfully surmounted this challenge. Two long tables anchor the center of the gallery and a shelf at one end support the two bodies of work, which are vastly different, but generated from the same premise. The pieces are not displayed by artist, but weave between each other stressing their commonality and discrete characteristics. This is an exhibit for looking. There are no labels (there is a list at the desk if you are interested), and no distractions.

Five years ago, sculptors Keiko Narahashi and Sarah Peters started a dialogue about sculptural representations of bodies, particularly heads and faces. They didn’t stop. As an experiment they photographed arrangements of Peter’s black-patina bronze figurines and Narahashi’s ceramics resembling face jugs and silhouettes. The Body Stops Here is a visual realization of that 2014 photo shoot, but updated to include recent works. The result is what could be described as a call and response that addresses everything from formal relationships about color, texture, and form to historical and contemporary influences that include global, folk, and pop culture. In addition, Narahashi and Peters perused objects that were both spiritual and functional such as totems, masks, and today, humanoids that mirror the human body. In a smaller space in the rear of the gallery, as part of the exhibit, many of their references are available for viewers to browse. The outcome includes sculptures that are hilarious while others speak to the power of sexuality embodied in characters ranging from Medusa to Princess Leia.

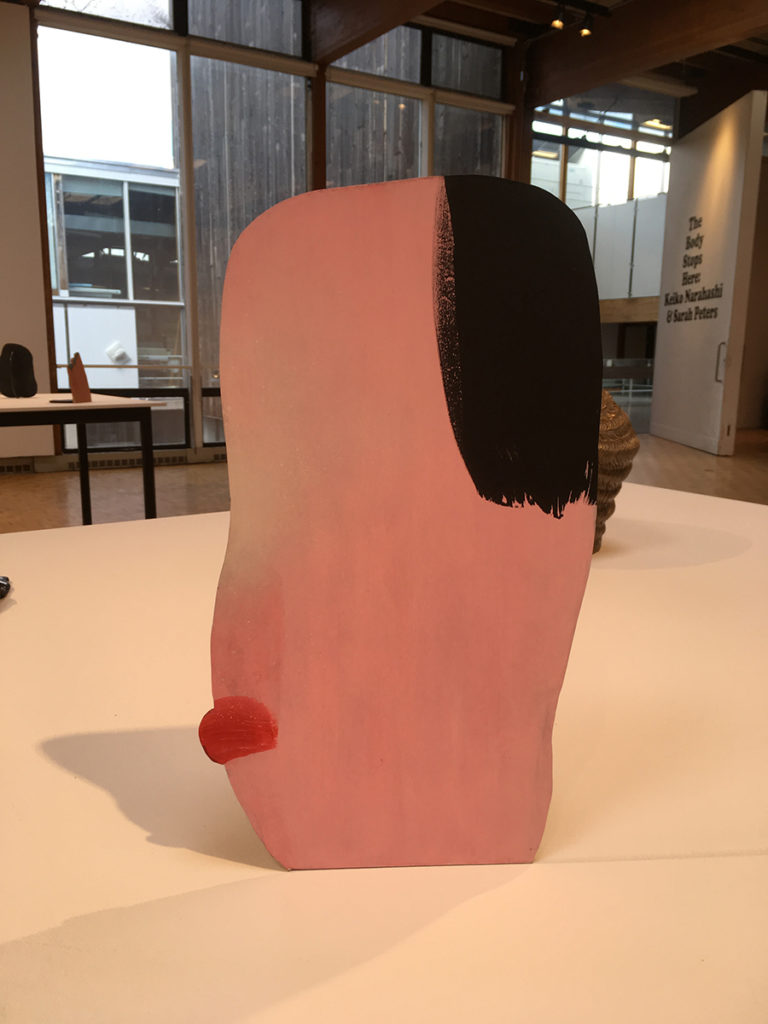

Keiko Narahashi’s works are simple minimalist pieces. Some are aluminum painted in bright pop colors such as pink, and some are stoneware glazed in deeply rich hues. The sculptures are constructed of flat pieces united by color. Due to the historical significance of the gallery, you can’t help but make the association between minimalist sculptors such as Anthony Caro, who also used flat shapes to successfully build intensely colored three-dimensional works, but there is something different here. Narahashi has imbued her work with a vulnerable content. The longer you linger you begin to see these are more than abstractions; these are silhouettes of the human experience that capture the schizophrenic nature of our expressions, both humorous and traumatizing.

One great example, Pink Pout, reveals that moment of anger and sadness, the state of being on the verge of tears, while looking ridiculously comical. Narahashi, born in Japan, has been influenced by everything from simple Korean and Japanese pottery to terrifying ghost stories of abused women seeking revenge to Jizo-sama, statues of a Buddhist monk, protector of deceased children, who is often adorned with knit sweaters, Hello Kitty toys at his feet to Harpo Marx. When you stare at this work, it all makes sense.

In contrast, Sarah Peters work initially appears to be traditional figurative sculpture. She is a master working with classic materials such as wax, clay, and bronze. This virtuosity allows her the freedom to sabotage the original intent of this style of work. When asked if she was undermining authority her response was, “Yes, by making the male figures puppets or ventriloquist dummies or giving them giant vaginas I like to imagine that I’m inserting myself into the canon when I distort classicism. I feel like an infiltrator. I enjoy that.” The daughter of a Baptist minister, she thinks of sculpture as speaking in tongues with her hands. Her interest in male authority figures comes from childhood experiences with the Christian church where, as in many other religions, a male figure represented authority and power. Peters’ heads are bronze, resembling Assyrian and Roman statues. The eyes are vacuous sockets similar to sci-fi movie humanoids. The hair on each bust is meticulously rendered, but absurdly exaggerated. Tripod (Animal), a bronze bust, is an example of the frightening twist she instills in each head. The empty eyes, the skull bisected, the narrowing jaw, the smooth patina of the bronze, all create the notion of a creature not human, but real.

This show is a thoughtfully curated exhibit in idyllic surroundings and demonstrates what contemporary galleries can do when extraordinary artists come together with astute curators.

The exhibit is on view at Bennington College, Suzanne Lemberg Usdan Gallery, until March 31

One College Drive, Bennington, Vermont, 05201, Hours: Tuesdays-Saturdays, from 1:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m.

You must be logged in to post a comment.