by Daniel T Cross; January 11, 2022

Sustainability Times; (CC BY-SA 4.0)

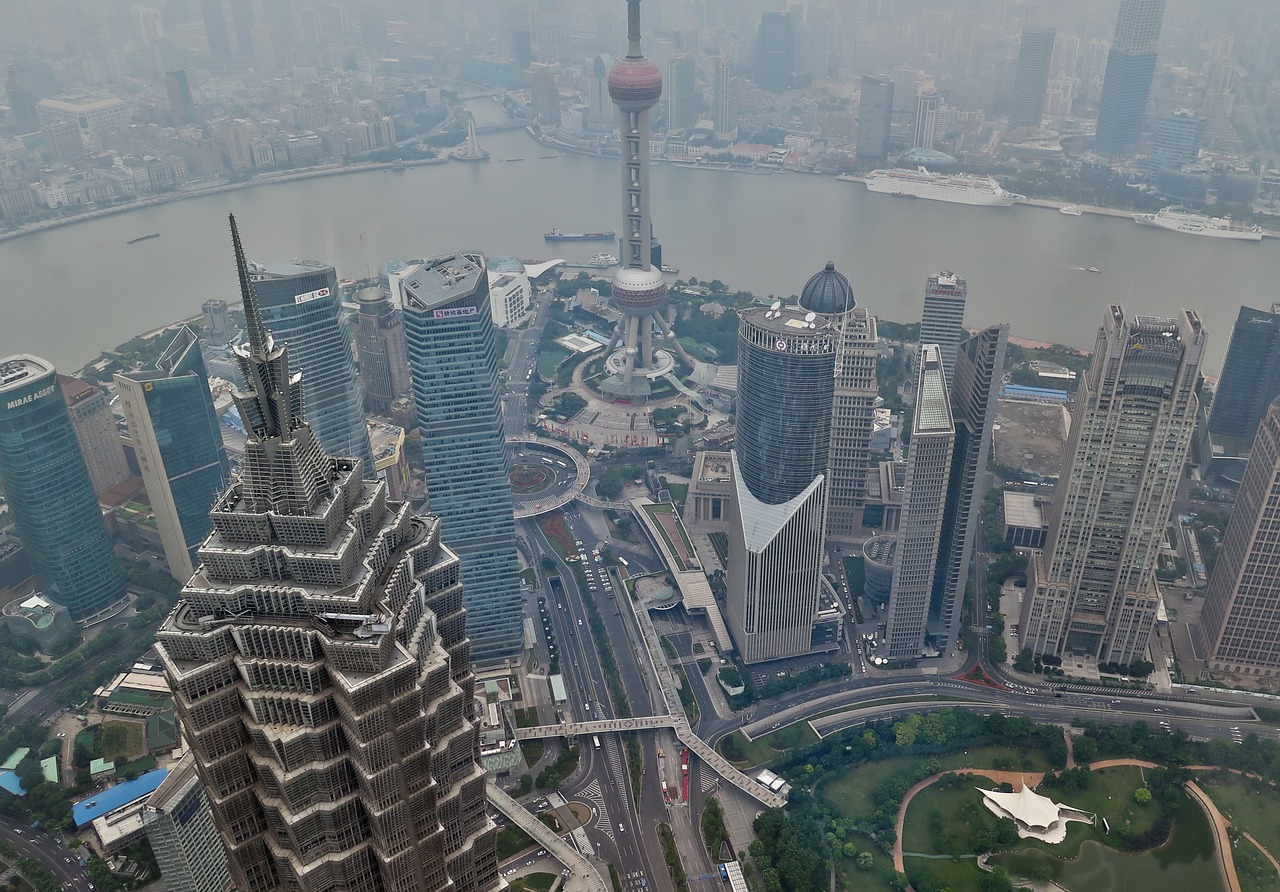

Some 2.5 billion people, or 86% of people who live in cities worldwide, suffer from varying degrees of air pollution. And many of them are at increased risk of cardiovascular, respiratory and other diseases.

This is according to a new study in the Lancet Planetary Health journal, whose authors found by help of their new computer model that in a large majority of cities worldwide levels of PM2.5 (a fine particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less) exceed those recommended by the World Health organization.

As a result, more than 1.8 million people die each year of various diseases caused or worsened by long-term exposure to high levels of air pollution, the scientists say.

“Although regional averages of urban PM2.5 concentrations decreased between the years 2000 and 2019, we found considerable heterogeneity in trends of PM2.5 concentrations between urban areas,” they write.

“Regional averages of PM2.5-attributable deaths increased in all regions except for Europe and the Americas, driven by changes in population numbers, age structures, and disease rates. In some cities, PM2.5-attributable mortality increased despite decreases in PM2.5 concentrations, resulting from shifting age distributions and rates of non-communicable disease,” they explain.

In most of the world’s largest cities air pollution can be especially severe, which is alarming given that already 55% of the planet’s nearly 8 billion people live in cities and their number is set to grow in coming years and decades. And as urban areas expand, so too does air pollution.

In some regions such as Southeast Asia levels of air pollution are becoming worse, with the region having seen a 27% increase in average population-weighted PM2.5 concentration between 2000 and 2019, the scientists found. “Deaths attributed to PM2.5 increased by 33% over those years, from 63 to 84 in 100,000 people,” they write.

During the same period African cities had an 18% decrease in PM2.5 concentrations and European cities had a 21% decrease while cities in North and South America had 29% decreases.

“This, however, did not correspond to the same level of decreases in PM2.5-attributable death rates on their own. This means that other demographic factors, such as an aging population and poor general health, are influential drivers of pollution-related death rates,” the researchers said.

Decreasing chronically high levels of air pollution will require forward-looking and comprehensive policies, the scientists say.

“Avoiding the large public health burden caused by air pollution will require strategies that not only reduce emissions but also improve overall public health to reduce vulnerability,” stressed Veronica Southerland, an expert at George Washington University in the United States who was a lead author.