Emmy Award–winning playwright, Joseph Dougherty, takes us on a heartbreaking and captivating journey that explores the notions of imagination, human deceptiveness, and trauma in his 2016 play, Chester Bailey.

Chester Bailey is a two-person play, directed by Ron Lagomarsino and starring real-life father and son actors, Reed Birney and Ephraim Birney. After a year of no live theatrical performances, Chester Bailey is the first indoor production to help Barrington Stage Company blaze back back to life after pandemic restrictions eased.

The plot revolves around a young, wounded World War II veteran, Chester Bailey (Ephraim Birney), who is currently being rehabilitated at a mental hospital in Long Island after losing his eyesight and both hands from a viscous attack by a fellow co-worker at a Navy-shipyard.

Although Doughtery does create an interesting storyline that deals with the challenges that one faces after experincing a traumatic incident, the pacing of the production was still rather slow which meant that you’re eyes can easily wander off the stage and lose track of what is happening.

Chester spends most of his time in bed reminiscing about his past life and is adamant that his eyesight will return and that his hands are still there. He also believes that love has entered his life, and throughout the play he keeps obsessively talking about a young woman he once met at Penn Station before his accident.

Chester is in denial of what has happened to him, and he needs someone to wean him away from his delusions, which is where Dr. Phillip Cotton (Reed Birney) comes in. Cotton’s job as Chester’s psychologist is to ground him back to reality.

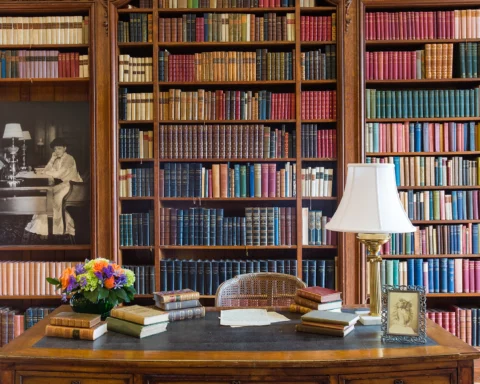

The setting of the play is simple, with audience eyes only drawn towards Chester’s hospital bed, Dr. Cotton’s desk, the purple multifaceted lighting in the background, and the darkened windows looming over Chester’s wheelchair. Even though Chester doesn’t look deformed on stage, the audience is still expected to picture him as this bandaged up man with no hands. The simpleness of stage props isn’t too overshadowing and fits in perfectly with the story because you really do get the sense that Chester is hospitalized and that the play takes place after the war.

Both Chester and Dr. Cotton take turns narrating back in forth to the audience about their past lives, previous troubles, and Chester’s accident. We learn that Chester wanted to enlist in the war, but his parents didn’t want him to, so instead they got him a job in the Brooklyn Navy Yards as a riveter, which is where he was assaulted. Dr. Cotton reveals that he has green-red colorblindness and is divorced, but is also having an affair with his superior’s wife. The two characters don’t start interacting with one another until halfway through the play.

The performances of the two leads were spectacular and the father-son duo makes the chemistry between the two characters even more convincing and relatable. You can tell right away that Chester Bailey and Dr. Cotton hit it off right away, and they talk to one another are father and son with a father-son intimacy.

The audience can figure out before Chester does that he is creating an imagined world for himself. So, we just end up following along with his illusions. “I started to see things in the whiteness. Shapes. Places where the white got a little thicker. I saw a rail and some bars coming down and I realized that was the foot of my bed and once I realized that it got clearer.”

Dr. Cotton is here to remind the audience of Chester’s condition, and that we shouldn’t underestimate his brain because we all create visible worlds for ourselves based off our imaginations. We all get raw information through our eyes, but it’s our brain that interprets what we see. Chester’s brain was creating an illusionary world without him physically seeing anything, because it was all in his head.

Chester Bailey will be playing indoors at the Boyd-Quinson Stage on 30 Union Street, Pittsfield Mass. from June 18 to July 3.. The play is 90 minutes long and begins at 7:30pm.