Portraying Holocaust survivor Eddie Jaku, Kenneth Tigar unleashes many powerful, memorable lines in Mark St. Germain’s The Happiest Man on Earth. I know the sentence that you’re supposed to take away at the end. The one that leaves with an optimism that if we all could just cling as tightly as we can to this axiom, maybe the future won’t be so bleak. I won’t be the one to spoiler the line, because it’s a moving one. And true. And may be the idea that saves the world.

But I’m just not there yet.

In this one-act, one-man powder keg of emotion, the line that continues to haunt me is this:

“We are German,” delivered with robust emphasis by Tigar.

This world premier runs through June 17 at the St. Germain Stage at Barrington Stage Company’s Sydelle and Lee Blatt Performing Arts Center. Directed by Ron Lagomarsino, this memoir in motion chronicles the harrowing years actual Holocaust survivor, Eddie Jaku, endured either imprisoned in, or escaping, the worst concentration camps in Europe during the Nazi regime. Brilliantly adapted from the memoir of the same name, the story arc, delivered directly through the fourth wall, immerses the audience in the fear and anguish of calculated genocide. We’ve come to expect that from survivor accounts. A theme that subtly runs through the show, however, is the stripping away of identity, done intentionally by the Nazi’s camp operators, and circumstantially by former neighbors, friends, and co-workers.

“We were German,” Eddie recalls his father declaring with pure immigrant patriotism. “We are German Jews.”

The expectation that once you adopt a country in your heart, and it adopts you within its polity, that the bond of mutual recognition and loyalty is fixed should be beyond question. The love, often relief and gratitude, for one’s new home weaves a durable new self-identity, and included in that is a national identity that becomes transgenerational. Tragically, collective, mass trauma also is experienced transgenerationally.

World Premier of The Happiest Man Alive by Mark St. Germain

CLOSES June 17

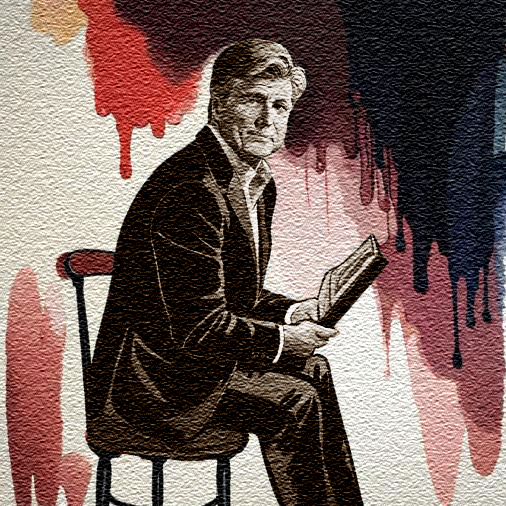

Kenneth Tigar, portrays Eddie Jaku in Mark St. Germain’s “The Happiest Man on Earth,” stage adaptation of Jaku’s memoir of the same title at Barrington Stage Company; photo by Daniel Rader.

As World War II rages on, and the Nazi’s “Final Solution” intensifies into a horror still difficult to internalize, more and more doors close to Eddie. Paths to safety are blocked. People he’d known since he was a child no longer saw him as a fellow German, but as a subhuman who, perhaps didn’t deserve extermination, but then again, didn’t rate an iota of compassion either. Perversely, Polish Jews in the camps were suspicious of Eddie’s German background, which further widened the rip in the image he had of his own identity.

But that’s what you have to do if you want to create an enemy class within your own borders. You have to find ways to cleave the target population away from the general public. That societal rip begins in abstract ways though propaganda, begins to solidify through news laws and codes, and reaches a concrete conclusion in the physical removal of the undesired to a distant location out of view of the loyal nationalists who might lose their appetite for genocide if they had to face the mechanics of it daily.

We arrive at this grim place early on in the play, and the near –action/adventure pacing at times is well-supported by deceptively minimalist scenic design by James Noone, lighting design by María-Cristina Fusté, and sound design by Brendan Aanes. Without giving too much away, it would not be a stretch to say that the set and effects in The Happiest Man on Earth squeezes more sense of place and drama than you’re likely to see created with light, a bit of sound, and some cleverly assembled lumber anywhere else this Summer.

Kenneth Tigar, as Eddie Jaku, takes you on an incredible tour of incalculable pain and loss, through constant fear, punctuated more than occasionally with humor that amazingly slices through an otherwise dismal backdrop. His performance is not the drone of an old man relating a string of personal anecdotes. Tigar is intensely physical — constantly moving and re-enacting scenes from his memory of the ordeal almost 80 years in the past. The dynamism of form is matched by intense swings of mood and emotion, at times rushing forward in white water rapids of monologue, at other times slowly to almost still water, melancholy nostalgia.

The role is grueling in all imaginable ways, (including being performed in a very dapper three-piece put together by Johanna Pan). I expected Tigar to be drenched in sweat by the end of the show, but he remained seemingly cool and in total control of all systems throughout.

This is the last weekend to see this masterpiece, and if you go, I encourage you to read a story from just this week in The Berkshire Eagle, concerning a 12-year-old attending Nessacus Regional Middle School in Dalton who harassed and terrorized his social studies teacher, Morrison Robblee, to the point that the teacher has quit is job and is seeking to relocate immediately out of the Berkshires. Robblee, who discussed being Jewish with his class could not have anticipated that a little boy would start “with insults in February, Robblee said, then [graduate] to jokes about the Holocaust, gas chambers and other aspects of Nazi Germany in his class.”

The article continues to explain that a few days after an ugly incident during Passover, “Robblee said the student handed him several drafts of a drawing that showed Adolf Hitler standing over a dead Jewish person, with heading along the top: ‘Sorry, Jew.’”’ The student called it an apology letter.”

News of this chain of openly hostile antisemitic behavior coming from a sixth-grade student follows quick on the heels of an incident in Lee Elementary School in which a publicly displayed art project displaying multiple swastikas, meant to illustrate evil. Andy Clark, who is Jewish, teaches English as a Second Language, objected to the display and took his concerns to the administration. Based on their response, Clark says he is leaving his position at the end of the school year this month.

In both situations, a Jewish person who had every right to feel as welcome as anyone else, quit their positions over concerns for their security. In the case of Mr. Robblee, leaving his job doesn’t feel safe enough. The Berkshires doesn’t feel safe enough. The Berkshires is a county, geographically, but it’s also a collection of cultural associations people tend to absorb even after living here just a few years.

What’s alarming about both circumstances is that the behavior of students was not enough, alone, to drive these teachers out of their careers and homes, but the actions and inaction of local government that utterly failed to address and mitigate environments that created deep personal distress for experienced teachers. If The Berkshire Eagle’s descriptions of both school district’s responses are accurate, an objective person couldn’t be faulted for wondering if the lip service paid to celebrating diversity actually provides cover for bias, at best, or latent antisemitism (at worst) within the power structure of these local schools systems.

In an era plagued by an expanding fascist movement worldwide, the significance of remembering and retelling the stories of the Holocaust remains as vital as ever. While survivor testimonies have played a crucial role in shaping our understanding of the Holocaust, a new play about this harrowing chapter in history offers a unique opportunity to engage audiences on a profound emotional and intellectual level. By delving into the depths of human suffering and resilience, The Happiest Man Alive serves as a powerful reminder of the atrocities committed in the past and the importance of remaining vigilant in the face of rising fascism. This theatrical triumph, which deserves to be extended another weekend, at least, comes at a time when an anxious America needs to sit up and listen to as many Holocaust survivor stories as still remain to be told, before the memories lose their power to warn us to the threats in our own backyards.