Behold! It is that time of year again. The autumnal wind rattling the air vents, the smell of rotting leaves, and the talk of Hallowe’en get-togethers as the perfect excuse to meet up with that friend you’d been meaning to hang out with for months.

But what about the themes and theatrics of it all? What is it about the season that is so empowering, and weird, and wonderful?

I write with the belief that the costumes and the decor are not merely ephemera, but symbolic of our psyche and society — central to a modern-day ritual.

The Celts celebrated Samhain, the old Gaelic festival marking the dark, barren winters. Allegedly, people wore costumes as disguises to ward off dangerous spirits. The belief that dead souls roamed free indicated a fragility of boundaries between the physical and spiritual world. Modern media builds upon this premise of Hallowe’en and liminality. This ranges from the adult horror American Horror Story: Murder House (2011), where the dead walk free on Hallowe’en, to the child-friendly Halloweentown (1998), whereby the holiday eases the crossing between the normal world and Halloweentown.

The superstitions associated with Samhain have transformed into a different form of ritual. Hallowe’en is still very much a pagan ‘festival’, except the emphasis on consumption, costumes, and aesthetics have diluted the attitudes towards the season. A juvenile, fun, and marketable spin on the ancient holiday is now the norm in the Western world, even with Samhain existing alongside it.

But, Hallowe’en is not merely sexy costumes, trick-or-treaters, or house eggers for the sake of it. Hallowe’en is its own modern ritual. While there is a lot to be said about trick-or-treating, here I focus more specifically on the Hallowe’en house party, a ritual among older youth.

Firstly, the idea of becoming someone else naturally appeals to the young or to those still exploring their identity. The combination of the popular holiday theme and the ‘house party’ involves all kinds of wonderful oddities. This state is liminal; you may be a sexy were-rabbit for the late-night karaoke, but that does not mean you are the sexy were-rabbit at the group hangover, with everyone drooling on your sofa.

Philosopher and critic Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory of the ‘Carnivalesque’ comes to mind here, as a concept which transcends eras. Bakhtin’s theory refers to the ‘carnival’ in a broad sense, relating to festivities and cultural rituals. The four characteristics include familiar and free interaction between people, eccentric behaviour, carnivalistic mésalliances (the uniting of opposing concepts – the spiritual and the physical, the rich and poor, the young and old), and profanation (a secular normalisation of obscenities, a disregard of the sacred).

Hallowe’en parties perfectly exhibit these four conditions. The removal of hierarchical barriers that would be in place in the school or workplace makes free interaction between people easier, effortless, and natural. Striking up conversation with strangers is normalised or even encouraged, meanwhile in other group settings or contexts it may be unwarranted. Within the Hallowe’en party, there exists a unique realm to practice this ritualised socialising.

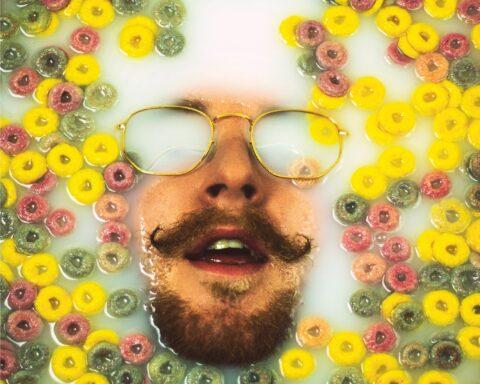

The ritual of Hallowe’en may also prompt eccentric behaviour, with people playing games, dancing, and drinking in unwearably revealing, camp, or even taboo costumes. Hallowe’en rejects the professional image of the day, thereby instilling a sense of profanation within the ritual. The joining of all classes of people, equalised through the campness and theatrics of their costumes, unites the party as one.

The party-goer as an individual wears a mask – much like the physical and symbolic mask of the carnival – not only through costume, but through the social expectations of dressing up, intoxication, moving one’s body, and socialising. This ritualistic performance makes the Hallowe’en party ironically religious.

Additionally, this climate of bonding, new experiences, and exploring the identity make it an excellent plot point in film and cinema. Coming of age films may utilise the ‘Hallowe’en House Party’ for plot development. In Mean Girls (2004), the Hallowe’en party scene explores aspects of character dynamics, turning points, and character motivations.

Protagonist Cady Heron arrives as a traditionally ‘scary’ zombie bride, whereas her peers come in lingerie and animal ears. This contrast then highlights Cady’s social naivete and her lacking knowledge of American teen trends. This tension between Cady and her social group is a set-up to a turning point in the plot: the audience finally sees the deceitful and sabotaging nature of Regina George as we see her steal Cady’s crush, Aaron Samuels. This then provides Cady’s motivation for revenge, which encompasses the one-eighty change in character essential to her character arc. All in all, I cannot think of anything better than an adrenaline-rushed Hallowe’en fest as a set-up for such a critical moment.

Society fears the monstrous, both external and internal. The horror genre plays on monstrous imagery to symbolise underlying societal fears. I, as the author of this piece, think this makes dressing up for Hallowe’en so liberating. On one hand, the costume is a mask, but it is also representative of the deviants within us. The horrific, the grotesque, the sexual, and even the camp are all social taboos in some way, in the primitive feelings of vulnerability they ignite. Hallowe’en celebrates this vulnerability, subverting our feelings of terror and awe of the sublime, or attraction to the sexual, or fear of the monstrous into good old-fashioned fun.

I find this empowering and oddly nurturing of our shadowed, passionate sides to ourselves. I love the fact that placing this ritual out of context is unsettling and amusing. I adore the profanity and the absurdity of Hallowe’en fashions, and how the adaption of this pagan festival has flourished among young people as a means for exploring themselves in relation to the world.

When we next get to celebrate Hallowe’en in whichever way we choose, party or not, let us remember Samhain, the Carnivalesque, and the primitive monstrousness in which we applaud, even if for one or a few nights only.

You must be logged in to post a comment.